European Heritage Days Article:

Ukrainian pre-war Mariupol: community initiatives to preserve and promote cultural heritage

European Heritage Days Article:

Ukrainian pre-war Mariupol: community initiatives to preserve and promote cultural heritage

Historical Dimensions of Mariupol

The current tragedy overshadows the city’s remarkable historical and cultural heritage.

Located on the northern shore of Azov Sea, at the mouth of Kalmius river, Mariupol and its neighbouring region has been a part of the steppe corridor, from the Ural Mountains to the Danube, for hunters and gatherers and then nomadic tribes for thousands of years.

The first settlement is dated 5 000 B.C. . Tall cattle breeders with European anthropological features lived on the high Kalmius right bank and buried their relatives on the opposite bank, where the ruins of Azovstal now stand. Excavated in the 1930s, their burial ground gave the name to Neolithic “Mariupol archeological culture”.

One of the keys to the puzzle of Indo-European and Indo-Persian origins may be found in the thousands of kurgans scattered around Mariupol and the region. Remnants of an ancient wheeled cart were found near the city, while 6 meters high kurgan is still standing amidst Soviet mass housing buildings. Traces of Scythians, Cimmerians, Sarmatians, Cumans, Tatars and Nogais have been regularly uncovered by archeological expeditions since 1920s.

In the 18th century, the Ukrainian Cossacks founded their permanent settlement at the river mouth. But the Russian Empress Katherine the Great radically changed its future. Upon her order, dozens of thousands Greeks were resettled from Crimea to North Azov region by the end of the 18th century.

Descendants of Ancient Greeks and the last heirs of Byzantine Empire made Mariupol their capital and have enjoyed significant autonomy until 1860s, sharing it with Italian and Balkan merchants. Mariupol Greek Arkhip Kuindzhi, the famous painter, “master of light”, made his compatriots known around the world.

But they were not alone on the Wild Steppe. In the 19th century, Mennonites and Germans from Prussia, Ukrainians, Russians and Jews founded dozens of rural settlements around Mariupol.

At the end of 19th century, massive industrialization transformed Mariupol into the city of open culture. French and Belgian engineers, American and German entrepreneurs, Polish doctors, Jewish traders and artisans, Ukrainian and Russian workers, among many others, were attracted by the booming metallurgical plants and the sea port.

The Bolshevik revolution and the following Soviet rule sought to erase pre-revolutionary historical memory and its representatives and plant so-called Soviet identity.

In 1938, Stalin’s “Greek Operation” killed thousands of Azov Greeks. Survivors hid their origins until perestroika times. Azov Germans were massively persecuted on the eve of the World War II. In October 1941, Nazi killed many thousands of Mariupol Jews. In 1948, Stalin stripped Mariupol of its historical name and named it “Zhdanov”, to “honour” his cultural “propagandist-in-chief”.

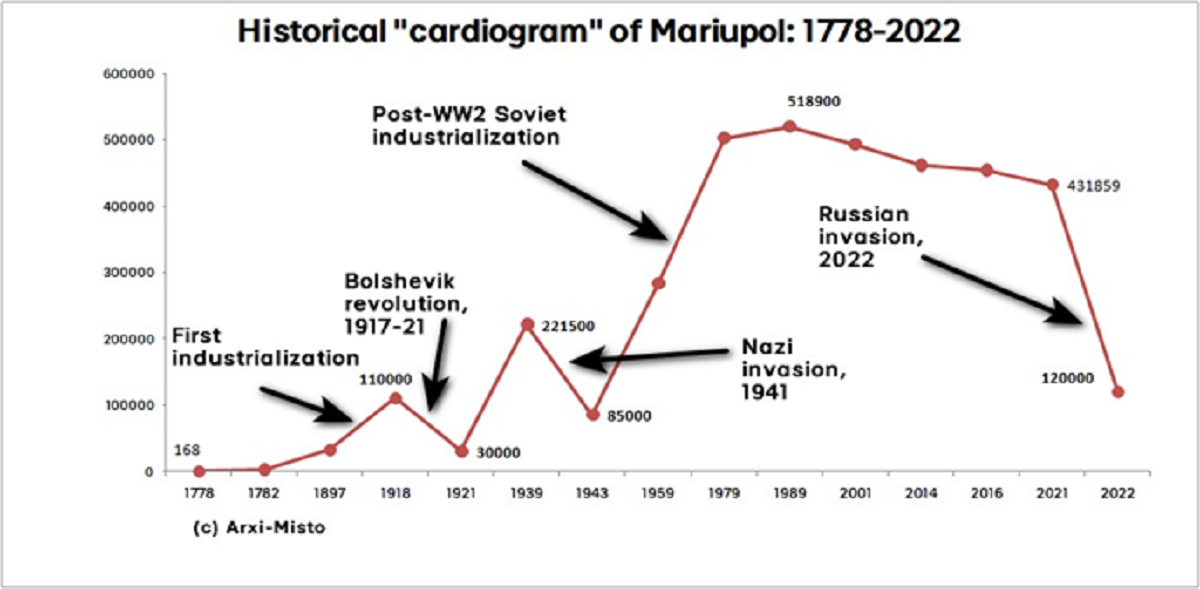

Post-WWII Soviet industrialization then boosted the urban economy and well being for decades. However, the influx of newcomers from all over the USSR made city dwellers with pre-revolutionary memories a tiny minority (see Diagram “Historical cardiogram of Mariupol, 1778-2022”).

Perestroika brought about a burst of cultural renaissance. City residents were among the first in the Soviet Union to return their city its historical name in 1989. However, hardships of post-communist transition have removed preservation and promotion of cultural and historical heritage from city agenda for years…

Mariupol Archeological Season 2018 (M.AR.S. 2018)

How to break down negative perceptions of the city? How to boost city residents’ interest towards ancient history?

These were questions our team members asked themselves in 2018. Low intensity fighting was going on close to the city’s boundaries. The city was perceived as dangerous, with Soviet style metallurgy like “Azovtsal” steel plant, a polluted environment, without any attractive historical heritage. City residents largely shared this perception and the majority of young people thought about leaving their “boring” city. We decided to leverage the potential of archaeology.

In cooperation with archeologists from the Mariupol State University, we organized an archeological expedition to the Bronze Age settlement near Mariupol, 40 kilometers away from the frontline. Our goal has been to involve volunteers from all over the country.

We designed a special promotion campaign. In Ukrainian social media, we targeted two key audiences: Ukrainians living in Central and Western Ukraine and young people in Mariupol. The title of the expedition reflected our key messages. On the one hand, it emphasized its exploratory nature by referring to the very popular expeditions to Mars. On the other, we did not hide the potential danger of going to an area very close to the frontline - Mars has been the Roman God of War.

For teenagers, we added clear references to Lara Croft and heroes of Jules Verne’s adventures studied by school pupils around the world.

No sensational findings were made. But the project has been successful. Ten volunteers from ordinary walks of life spent their own money for travelling and came from Lviv, Kyiv and other large cities (we covered only accommodation at expedition’s camp). National and local TV channels made special broadcasts. Mariupol parents brought their children to spend one day at the excavation.

Key lessons learnt have been clear. If you would like to make the heritage “living”, you should give the people an opportunity to explore it by their own hands and minds!

Much insight was gained from the participatory and team-based nature of the expedition. If you care about the sustainability of your project, try to foster human networks around it. We succeeded. We were not able to test their strength as Covid pandemics thwarted continuation of M.AR.S. But then, after the Russian invasion, volunteers of the first expedition contacted Mariupol members with proposals of help…

Finally, if you would like your heritage project to be realized, you should consult and involve all possible stakeholders. In the case of M.AR.S. 2018, the Ukrainian military authorities gave their permission and guaranteed that fighting escalation was not foreseen and that there would be no threats to lives of expedition members. Civil authorities of all levels provided logistical support.

Mariupol Light Necropolis: cleaning, restoring, exploring

How to turn historical cemetery-dumping ground into open air museum?

Under the Soviet Union, an overwhelming majority of cities in Eastern Ukraine lost their historical cemeteries. They were replaced by massive housing or erased as reminders of the tsarist past.

Mariupol has been lucky. Its “old city cemetery”, established by 1811, and the Jewish cemetery (1870-s) survived. Today the first one is located in the city center (15 minutes walk from Drama theatre).

However, their magnificent sculptures and monuments were ruined and their abandoned territories turned into dangerous dumping grounds.

The old city cemetery (Mariupol Necropolis per se) has become the last home for hundreds of thousands of Mariupol residents – from its first Greek founders, Italian merchants, Belgian engineers, and Polish intelligentsia to soldiers of WWII and builders of Soviet industrial giants. The Jewish cemetery preserved the memory of once-flourishing Jewish community, with unique matzevas.

As an outcome, many residents started perceiving cemeteries as unique city landmarks. The mayor’s office approved plans to make them open air museums.

Before the Russian invasion, we planned to develop the new concept of the historical cemetery. Following the ideas of l’Ecole des Annales and using online technologies, we thought about using them as a gateway to explore the world of any person buried there (their music, beliefs, ways of living, dances, books etc.), from the first Greek inhabitants to workers at Soviet factorie.

As elsewhere in Europe, Ukrainian cemeteries are strictly regulated, with criminal penalties for damaging graves. Dozens of thousands of descendants have their legitimate interests there.

Under such circumstances, transparency, openness and accountability were key principles of our work. Any action was documented with photos and videos. They were published in the special Facebook group. We routinely reported about the use of any resources raised by crowd funding efforts.

Another lesson is about an importance of shaping perceptions. Even the most neglected object of cultural heritage can be brought back to the life, if you will find its unique features resonating with people’s minds.

We rejected the term “Old city cemetery” and insisted opted for “Necropolis”, with its clear connotations of “noble Antiquity”. In contrast to its perception as dark and dangerous place, we named it “Light Necropolis” after the installation of solar lanterns on the cross of the shrine. There was an unexpected outcome: When blockaded Mariupol has been put into total darkness, and the Necropolis has been the only place with some light at night! To enhance the “garden cemetery”, relic trees like sycamore were chosen.

Then, our main focus has been rather on people and stories of their lives than on Byzantine plates of Greeks’ tombs or sculptures. We try to find human story behind any heritage object and tell it to the people.

To sum up, here are the lessons from our experience:

- Give the people an opportunity to become Jean-Francois Champollion, Heinrich Schliemann or Lara Croft

- Sustainable heritage projects require human networks with common team spirit. Shape and support them!

- Consultations with and involvement of all stakeholders are mandatory

- Transparency and accountability should be obligatory principles if you work within a sensitive environment and/or attract crowd funding

- Even the most neglected object of heritage can be brought back to the life! Just open up your mind and be creative in shaping people’s perceptions

We are happy to share our experience with hope that it will be useful to other heritage practitioners all over Europe. We are open to further share our experiences and realize joint projects with European partners, in particular, about post-war restoration of Mariupol’s cultural heritage.

Author:

Andrii Marusov

Director

Mariupol cultural non-profit “Arxi-Misto”