About a Contemporary Concealment: Reversing Archaeology and rescuing the present culture

Dimitris Alitheinos, a contemporary artist mainly known for his concealments all over the world, has implemented his 88th concealment in the external space of the former Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki (nowdays MOMus – Museum of Contemporary Art), only six months before the millennium. The artist’s gesture, largely symbolic and universal, raise awareness of the great dangers that threaten the planet concerning not only the future but primarily the present, the imperative of saving human culture and art, which, as he claims, is the main carrier of human memory. The concealments of Alitheinos propose a kind of “reverse archaeology”, a process in which material objects, instead of being unearthed and brought to light, are encased and buried, protected from oblivion. By his concealments - now exceeding the number 232 – Alitheinos creates a dialogue between the visible and invisible, the hidden underneath and the revealed in light, the memory and the oblivion, the local and the universal, the present and the future.

The museum which hosts the 88th concealment is situated where the Thessaloniki International Fair Trade is being held in annual basis, a kind of urban gap that during ancient and roman times used to serve as the eastern cemetery, outside the city walls. The museum building incorporated at least in three different rooms the archaeological findings revealed during the excavations for the museum building expansion which afterwards were preserved in situ. Since no systematic archaeological research was conducted during the foundation of the rest buildings and pavilions and of the Trade Fair Center, the only space where Heritage and Past seem to coexist with the Present is the Museum of Contemporary Art. Alitheinos’s 88th concealment with its symbols referring to Luck, Time, Fate and Destiny carved on a table, manages to comment the multidimensional functions of this site during time and remain relevant and diachronic.

It was just before the turn of the millennium, in June 1999. Hewanted to preserve something from the culture of the 20th century for future generations. This would mark his 88th concealment - the 88th time he entrusted the earth with a symbolic object, believing in ground’s power to protect, preserve, and eventually pass on fragments and records of human civilization to future generations. His artistic practice, marked by numerous concealments in various locations around the world over the years, functioned as a kind of "reverse archaeology" - a process in which material objects, instead of being unearthed and brought to light, were encasedand buried, protected from oblivion.

In the same city, Thessaloniki, he had carried out his first "maiden" concealment in 1981along the waterfront. “I dug, changing what had been visible for centuries into invisible.Βy hiding the image I released its energytransforming absence into a perpetual broadcast of myth”, he recalls.

This time, however, the proposed location was the courtyard of Τhessaloniki’s only contemporary art museum at that time. Ideally, he would have preferred to execute his project next to a segment of an ancient stone-paved road, which had been unearthed during the museum building architectural expansion in 1997. That was the year Thessaloniki was named European Capital of Culture, securing the necessary funding for the museum’s foundation of new rooms. Thanks to the museum’s administration and staff and in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities, this rare archaeological find - part of the ancient road network discovered outside the city walls - was integrated into the museum’s structure and remains visible to visitors to this day.A few years later, in 2002, two more areas within the museum would compel visitors to look downward, towards the floor, where through transparent glass panels they could gaze upon the burial structures and remains uncovered during excavations. These toowere preserved in situ and incorporated into the building, initiating an ongoing and timeless dialogue between cultural heritage and contemporary art. Only agrave of a little child with the 60 clay oxen figurines, aswell as the statuette of Telesphoros (a deity of the cycle of Asclepius represented as a child on cloak and hood) and the obolon of Charos (the coin with which to pay the ferryman, Charon, to carry the dead to the Underworld) is now included in the exhibits of the neighboring Archaeological Museum.

All of this was possible because the broader area where the museum stands, had for centuries, served as Thessaloniki’s eastern cemetery - one of the city’s two main burial grounds outside the walls. It was in significant use during Late Antiquity and the Roman period, mainly from the 4th century BC to the 3th century AD. In more recent times, scattered burials of the Muslim community were found in the upper soil layers. Although the city expanded beyond its walls from the late 19th century onward, this area remained undeveloped as an urban gap,moreoverbecause the post-1917 fire reconstruction plan had designated it as a metropolitan park. Thus, in 1950, following World War II and the Greek Civil War, when the Thessaloniki International Fair sought a new venue, it was naturally drawn to this site. A former cemetery - once a space of silence and passage - became synonymous with the city’s most significant annual commercial and social event, which brings Thessaloniki into the spotlight of economic and political news. Every September that TIF is held, the country’s entire political leadership gathers here to deliver speeches outlining national policies, developments, and future prospects, especially within European Family.

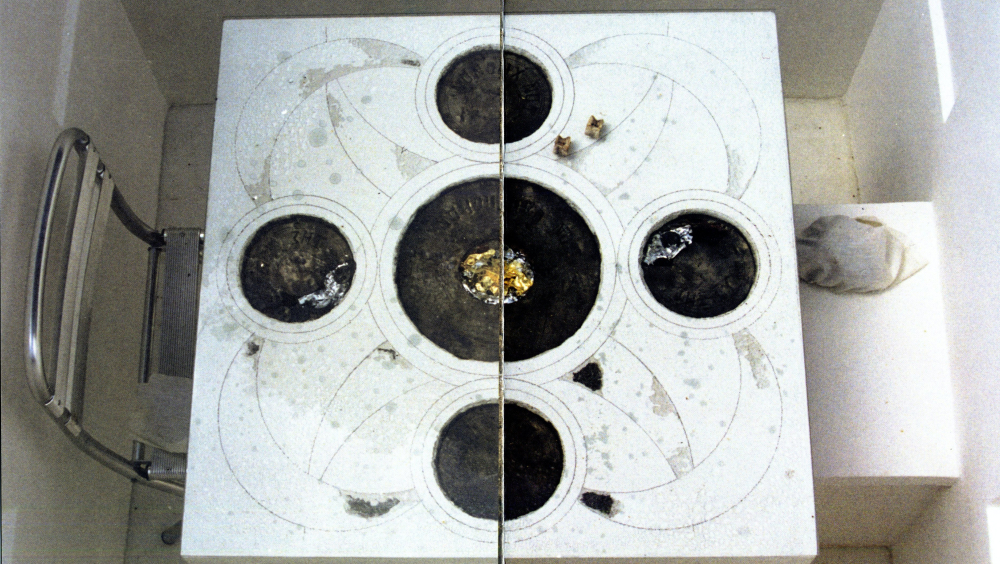

Considering all these dimensions and under the scorching mediterranean summer sun, the artist opened his excavation in the museum’s courtyard, carefully preparing what he would place inside. Typically, each concealment required about a week to complete, allowing the public to observe the process. This time, the artist chose to place a cube-shaped room, measuring 180 x 180 x 180 cm, where a table and two chairs stood inside, insinuating a conversation between two companions at a meal. On the tabletop, in place of plates, he engraved four circles with symbols and words: Of Luck, of Time, of Fate and of Destiny.

The museum whose external space hosts the 88th Concealment of the artist is the former Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art now belonging to the Metropolitan Organisation of Museums of Visual Arts of Thessaloniki (MOMus).It was found as an initiative of art lovers, immediately after the catastrophic earthquake of 1978, with the encouragement of the gallerist Alexandros Iolas who promised, and finally signed, the first donation of 47 artworks.

The artist who implemented the 88th concealment in the grounds of the museum is Dimitris Alitheinos, who was also a candidate for the Melina Mercouri UNESCO Prize for the Safeguarding and Management of Cultural Landscapes. He once conceived and realized the project of concealments - now exceeding the number 232 - due his concern about the dangers that threaten the planet with annihilation, such as the nuclear threat and the ecological disaster. The only evidence that comes to light for the entire series of hidden works are the cards sent by the artist, which always contain a reference to the specific place and time.

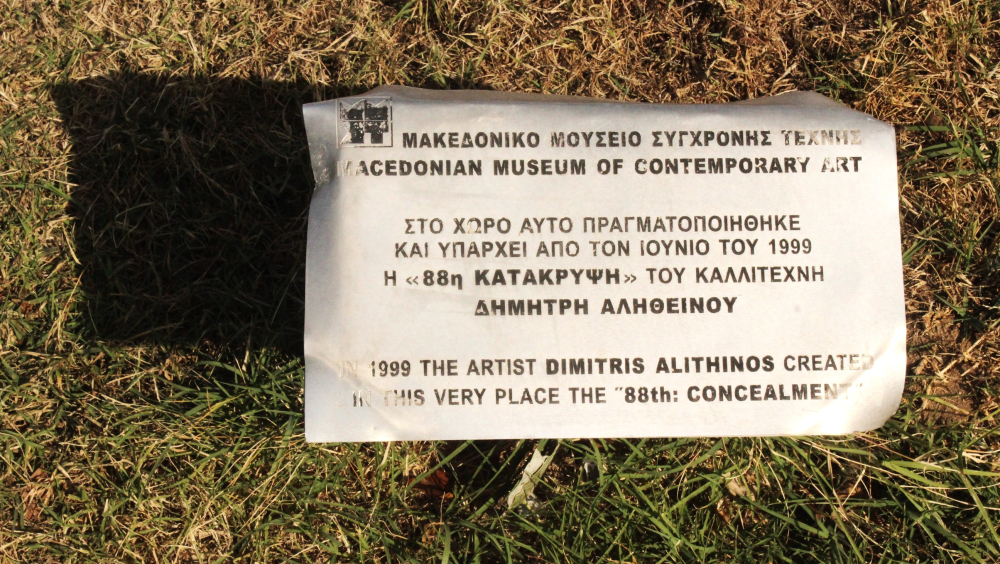

Τoday museum visitors, especially young, continue to be surprised by this “hidden” creation. If no one points it out to them, they might easily overlook the small metal plaque identifying the concealment. The artist’s choice unsettles them, raising questions: How can a visual artwork be completely hidden from view? Many of them need to see photographs to discover what lies beneath. Eventually, as they come across the worldwide map of concealmentsthey are left speechless. And then comes the inevitable question: What will happen in the future? Will there ever be a day when all the concealments are unearthed simultaneously worldwide?

The foundation of Thessaloniki’s International Fair on a site that used to serve as a cemetery, not only in antiquity but even in recent times, presents relevant and diachronic challenges which traverse time, space, nations and countries. The annual TIF’s implementation is the city's most prominent commercial and economic event, oriented towards future, development and innovation. It is accompanied by political announcements regarding the country's course within the framework of the United Europe and its future priorities. Regarding the site itself though, it is interesting that since no systematic archaeological research was conducted during the foundation of its pavilions and buildings, an important part of the findings that would have offer precious information about the communities that once inhabited the city, was lost. Heritage and Past seem to have managed a balanced coexistence with thw Present only within the premises of the Museum of Contemporary Art, where the remainings of the archaeological research were preserved in situ creating a constant dialogue with contemporary exhibits.

Dimitris Alitheinos’s 88th concealment within this larger area constitute a gesture largely symbolic and universal which manages to “condense” the above problematic of managing Heritage and contemporary perspective. The struggle to balance between the historical heritage and the future integration, consist a diachronic challenge for all the European Union Nations. Moreover the concealment highlights interesting poles between the visible and invisible, the hidden underneath and the revealed in light, the memory and the oblivion and raises awareness of the great dangers of the present, as the threat of environmental destruction, an issue that is constantly in the agenda of EE. Thus they do not only concern the future but primarily the present, the imperative of saving human culture and art, which according to the artist is the main carrier of human memory.