Anna Perenna and Aesculapius

This storytelling is the work of a group of five students and young scholars in Classics (Ludovico M. Bevilacqua, Eleonora Boscolo, Davide Pettenò, Giulia Vettori, Davide Zennaro), who participated in an intensive workshop in ancient Roman epigraphy under the auspices of the Ca' Foscari University of Venice and the Association Internationale d'Épigraphie Grecque et Latine (AIEGL). The workshop took place in September 2021 in Feltre, a small town located at the foot of the Italian Dolomites and once a flourishing Roman settlement, called Feltria.

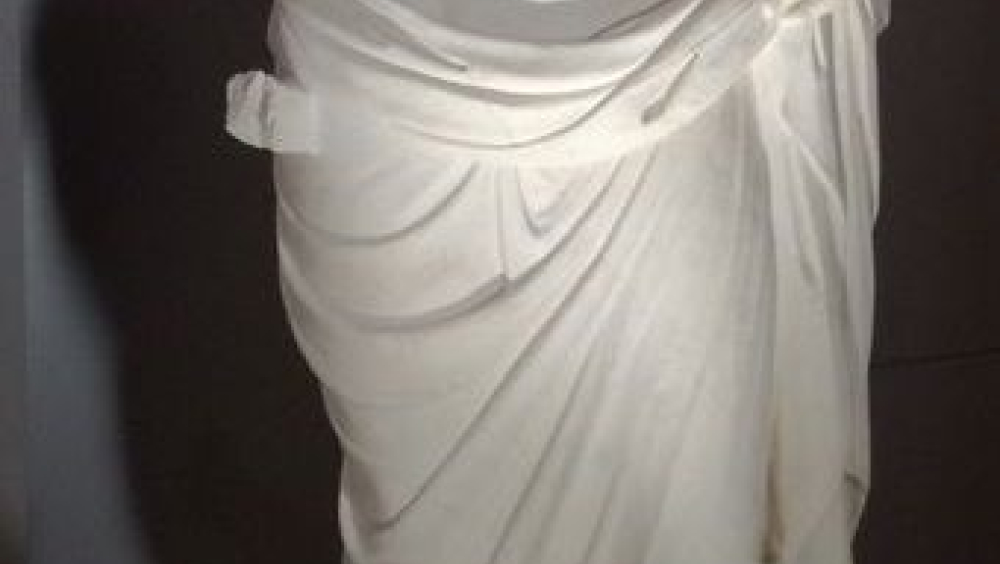

Our storytelling consists of a dialogue between the statue of Aesculapius, the ancient god of medicine, and the altar of a little-known Roman female deity, named Anna Perenna. Both monuments can be viewed in the same room of the local Archaeological Museum in Feltre. Our idea is to offer a combined experience of different multimedia elements. After being recorded, the dialogue will be reproduced in the space where the two monuments are exhibited. A spotlight will be used to put complete attention on the monument which is speaking at the time. In the background, a sound of flowing water accompanied by zither notes will be audible.

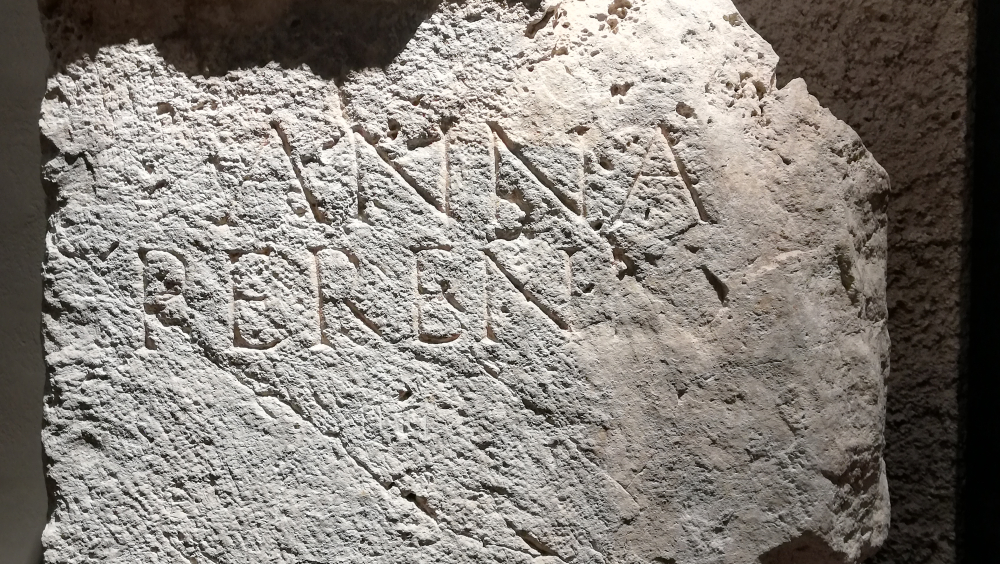

The dialogue begins with the god Aesculapius noticing that a new monument was placed in his own room. He immediately begins to be puzzled and asks the other monument for its identity. He discovers that the latter is an inscription to Anna Perenna, carved on a votive altar.

The dialogue is based on satire and consists of an exchange of jokes between the two deities, who engage a playful dispute to determine who is the most important and popular among them. Aesculapius, with his shiny and, in his view, very charming white marble body, now finds himself having to share the room with another monument. Anna Perenna replies without hesitation by asserting her role as a patroness of the Ides of March, just like Father Jupiter. She was the tutelary deity of the fertility of fields and of the rebirth of nature. She describes the festivals organised in her honour, making Aesculapius envious that he was not there. The dialogue ends with an acknowledgement of the situation: after all, both monuments already shared the place where they were found: the archaeological site of ancient Feltria.

ANNA PERENNA AND AESCULAPIUS

Introduction

This storytelling is the work of a group of five students and young scholars in Classics (Ludovico M. Bevilacqua, Eleonora Boscolo, Davide Pettenò, Giulia Vettori, Davide Zennaro), who participated in an intensive workshop in ancient Roman epigraphy under the auspices of the Ca' Foscari University of Venice and the Association Internationale d'Épigraphie Grecque et Latine (AIEGL). The workshop took place in September 2021 in Feltre, a small town located at the foot of the Italian Dolomites and once a flourishing Roman settlement, called Feltria.

Our storytelling consists of a dialogue between the statue of Aesculapius, the ancient god of medicine, and the altar of a little-known Roman female deity, named Anna Perenna. Both monuments can be viewed in the same room of the local Archaeological Museum in Feltre. Our idea is to offer a combined experience of different multimedia elements. After being recorded, the dialogue will be reproduced in the space where the two monuments are exhibited. A spotlight will be used to put complete attention on the monument which is speaking at the time. In the background, a sound of flowing water accompanied by zither notes will be audible.

The dialogue begins with the god Aesculapius noticing that a new monument was placed in his own room. He immediately begins to be puzzled and asks the other monument for its identity. He discovers that the latter is an inscription to Anna Perenna, carved on a votive altar.

The dialogue is based on satire and consists of an exchange of jokes between the two deities, who engage a playful dispute to determine who is the most important and popular among them. Aesculapius, with his shiny and, in his view, very charming white marble body, now finds himself having to share the room with another monument. Anna Perenna replies without hesitation by asserting her role as a patroness of the Ides of March, just like Father Jupiter. She was the tutelary deity of the fertility of fields and of the rebirth of nature. She describes the festivals organised in her honour, making Aesculapius envious that he was not there. The dialogue ends with an acknowledgement of the situation: after all, both monuments already shared the place where they were found: the archaeological site of ancient Feltria.

A Dialogue between Aesculapius and Anna Perenna

AESCULAPIUS: It seems that the last visitor has also left the hall for this evening. And what a fortune! Just today the museum staff brought in a new monument, right here in this hall, to keep me company. I am really curious to know who it is. Hey you! Yes, you standing in the corner. Can you hear me? Sorry, but I can't see you very well, for thundering Jupiter! As you can see, I lost my head several centuries ago!

ANNA PERENNA: Ha! You are complaining about losing your head! I am, instead, only an inscription carved on a votive altar! It is already a miracle that I can hear you.

AESCULAPIUS: I seem to recognise your voice, now that I hear you, but yes, yes, of course, I must have met you once, during my long existence: you are, you are....

ANNA PERENNA: Anna Perenna!

AESCULAPIUS: Anna Perenna? I have never heard that name. You must be a minor deity!

ANNA PERENNA: Call a minor deity your father Apollo, dear Aesculapius!

AESCULAPIUS: Well, these are strong words to be pronounced by a votive altar, dear Anna Perenna! At least, I have an almost intact body, made of shiny marble, and a rather fascinating one, I dare say!

ANNA PERENNA: Ha, by Hercules! Your marble robe may be fascinating, and you may even have an almost intact body, which I don't, but your memory is certainly not intact, since you no longer have a head! In fact, you do not even remember that long ago we both stood by those great Roman buildings of this city, the ancient Feltria, which are now under the present Christian cathedral, in a so-called "archaeological area", according to the mortals.

AESCULAPIUS: Don't talk to me about Christians! They were probably the ones who took my head off, although frankly I don't remember exactly, ... just as I don't remember you at all! Were we really standing close together? I remember, yes, a big building, but there were so many statues and so many altars all around...

ANNA PERENNA: This is incredible! But how can the god of medicine forget what he has lived through?

AESCULAPIUS: But come on, who do you think I am? Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory? I am much older than you: clearly, some details must have slipped away from my mind, after almost three thousand years of life. Please, show some respect!

ANNA PERENNA: Oh, by all gods! No, you are not older than I am, dear Aesculapius. I was a much-worshipped goddess in the earliest stages of the history of Rome, when it was still a small city in Latium, before it set out to conquer the world. In those days, you were worshipped mainly in Greece, and Italy was not your concern. Do you remember the plague that struck Rome in 291 BCE? It was then, after consulting the Sibylline Books, that the Roman Senate decided to build you a temple.

AESCULAPIUS: Oh, that I do remember! The Romans came to Epidaurus to take back a statue of mine to their city. And my serpent, of which here you can see only a small part of its white marble coils on my right, dived into the waters of the Tiber, headed towards the Tiber Island, and right there, by my will, the Romans built my temple. Anyway, from that time on my cult gradually spread from Rome to Western Europe. Ha, what glorious days! At that time there was much more work than today! Since we have all had to retire, and nobody remembers us old gods any longer!

ANNA PERENNA: Ha, don't tell me! At least your cult has developed to such an extent that you are a well-known god even in this era, but who remembers me? And yet, I was once an important goddess. Just think that I was the patron deity of March 15th, that is the Ides of the month, just as Jupiter himself was!

AESCULAPIUS: Is that so? Patron of the Ides of March, like Father Jupiter?

ANNA PERENNA: Indeed! The festival in my honour used to take place at the beginning of the Roman year. Not only was I the patroness of the New Year, but my divine prerogatives were also related with the cyclic renewal of the natural world. After all, in mid-March, spring begins to blossom, and I was worshipped precisely as the tutelary deity of the fertility of fields and of the rebirth of nature.

AESCULAPIUS: Interesting, but tell me, what did your festival consist of, precisely?

ANNA PERENNA: Ha, if you only knew, it was the best feast ever! People gathered in a sacred grove, dedicated to me, at the first mile of the Flaminian Way, on the banks of the river Tiber, and there, during the festivities, I was offered abundant libations of wine to celebrate the arrival of the new year and spring, in an atmosphere full of joy, rhythmed by chants, mimes and dances. Moreover, precisely because I preside over the new year, during the celebrations, the Romans would say to each other: Anna ac Peranna!, that is "may you spend and fulfill the year well!".

AESCULAPIUS: If I may ask you... why that particular location?

ANNA PERENNA: It was a symbolic choice: the location outside the city's sacred precinct recalled the isolated place where young Roman women had to stay to ritualise their change of status.

AESCULAPIUS: In what sense? What change did they undergo?

ANNA PERENNA: Don't worry! It was a natural change. During the year, some girls witnessed their first menstrual cycle and thus passed into adulthood. Obviously, the proximity of water was a must! It helped to recreate the symbolism of purification.

AESCULAPIUS: And what did you do?

ANNA PERENNA: I committed to be their guide throughout their initiation. I helped them to become aware that they had reached their sexual maturity.

AESCULAPIUS: So, was it a feast for girls only?

ANNA PERENNA: No, it was an inclusive feast! I was accompanied by Liber Pater, who followed young men as they went through their transition of becoming iuvenes. The feast celebrated the awareness of having become adults. But, like I said, the event was not just symbolic... I can assure you that it was a lot of fun!

AESCULAPIUS: Well, it must have been a great feast! Yet, I have never heard of it...

ANNA PERENNA: This is because, as I told you, my cult was developed above all in the most ancient times and limited to the area of Rome. Right there, in fact, there was a water source dedicated to me, which was used since the fourth century BCE. Magical practices were common at the time, and it is by no coincidence that my worshippers used to throw coins into my fountain for good luck. They also threw clay lanterns and tabellae defixionum. Do you remember them, my dear Aesculapius? They were those little lead foils where the Romans used to engrave curses to be cast on their enemies...

AESCULAPIUS: Of course, of course, I remember them! Those struck by the curses often invoked me to heal them! But tell me, if your cult was mainly located in Rome, where this spring of water was, why is there an altar of yours right here, in Feltria?

ANNA PERENNA: Of course, yours is a legitimate question, but you are asking me to remember events that currently slip away from my mind...

AESCULAPIUS: Ha! And then you tell me that my memory is not intact! You do not even remember what you are doing here!

ANNA PERENNA: Actually, I only have a rough idea of it. I know for a fact that the ruling class of Feltria had fairly close relations with the city of Rome. It is likely that a member of some of the most outstanding local families must have seen my source, where votive altars similar to this one were offered in my honour. So, once he came back here, he dedicated this altar to me, perhaps assimilating me to some other local divinity, whose features resembled mine, but whom I do not know.

AESCULAPIUS: A more than plausible assumption I would say, dear Anna. I must say it was a very pleasant conversation I had with you, we both brought back memories of the good old days!

ANNA PERENNA: Oh yes, at least from now on I shall have someone to talk to. Now I shall say goodbye and try to get some sleep. You know, I feel all my almost twenty-five centuries of existence!

AESCULAPIUS: Don't tell me! Good night, Anna!

ANNA PERENNA: Good night, Aesculapius!

AESCULAPIUS: Anna? Are you still awake?

ANNA PERENNA: Yes! Tell me, why can't you sleep?

AESCULAPIUS: Ever since we started talking, I have been hearing a continuous noise. It sounds like water running, as if there were a country stream right here, inside this room!

ANNA PERENNA: Oh yes, I am sorry... I had that sound put in! As I told you, I'm a nymph and I'm so related to water that this sound alone calms me down. I hope that it does not bother you! Trust me, it will relax you too! Just listen to it and you will soon be able to fall asleep. Would you like me to switch it off? Aesculapius? Can you hear me? I think that he has already fallen asleep ...

These findings are displayed at the Archeological Museum in Feltre, the ancient Feltria, a small town at the foot of the Italian Alps, near the Via Claudia Augusta, the ancient Roman road which connected Altino (ancient port near the future Venice) to Augusta Vindelicorum (now called Ausburg in Bavaria). Feltria was once a flourishing Roman settlement and an important crossroads for trade and people in transit to and from Northern Europe through the Brenner Pass.

We believe that the Statue of Aesculapius, the ancient god of medicine, dating back to the II century AD and the votive altar of Anna Perenna (I century AD) can be representative artifacts of the prechristian Roman culture, which is at the basis of modern European culture. The purpose of this simplified dialogue is to make comprehensible to visitors of all ages the prerogatives of these two divinities and also make them realize how strong and widespread the Roman culture and traditions were in everyday life, also in the smaller localities of the Empire.

With the storytelling modality we hope to make ancient history more interesting and accessible to everyone, to enable all Europeans to discover their roots.