FIBRANET, the textile fibres that connect us all

FIBRANET (FIBres in Ancient European Textiles) was a research project that investigated the fibres used in textile production in Europe from prehistory to the Roman Empire. Knowing what type of fibres a textile is made of is very important for archaeological studies, as it reveals cultural, socioeconomical and even palaeoenvironmental information. The easiest way to achieve fibre identification is by studying the fibres’ morphology, which is their shape and form, under very high magnifications. However, this is not always a straightforward task, as there are two factors that might complicate the task considerably. The first is that people in Antiquity would have used any type of fibre available to them locally to make textiles, handing down to us a huge variety of fibres with different or not so different morphologies, found in excavations. To address that, we collected a large number of plant and animal fibres from all over Europe. The second factor that makes fibre identification challenging is that due to their organic nature, textile fibres are inherently extremely sensitive to the degradation mechanisms that take place during burial, which more often than not affect the fibres’ morphology to an unrecognisable degree. Therefore, we designed degradation experiments to simulate the conditions under which textiles have been preserved across Europe. Samples of all fibres collected and experimented with were studied under optical and scanning electron microscopes at longitudinal views and cross-sections. The results of this research, like fibre images, cross- sections and relevant references have been stored at an on-line - freely accessible database, where the end user can make correlations and fibre identification of their own finds.FIBRANET investigated, synthesised old and new knowledge and produced data for textile fibres across Europe, and an openly accessible research tool, the open access database.

FIBRANET (FIBres in Ancient European Textiles) was a research project that investigated the fibres used in textile production in Europe from prehistory to the Roman Empire. Knowing what type of fibres a textile is made of is very important for archaeological studies. Archaeological textiles are made of natural fibres, mostly organic that come from plants or animals, hence textiles bear evidence of agriculture and stock-breeding and the climate in which these were grown and bred. Different techniques have been applied to process and subsequently spun or splice fibres to make threads, thus bearing evidence of technological advances. The choice of fibres used to make religious, ceremonial or heirloom textiles further provides us with social and anthropological evidence. Textiles are easily transportable artefacts and have traveled along the endless string of diverse cultures through various trade routes. Along their way, textiles influenced different civilisations, with their patterns, technological advancements and materials. Therefore, textiles have been carriers of cultural identity and express advances in craftsmanship and the arts. The easiest way to achieve fibre identification is by studying the fibres’ morphology, which is their shape and form, under very high magnifications. However, this is not always a straightforward task, as there are two factors that might complicate the task considerably. The first is that people in Antiquity would have used any type of fibre available to them locally to make textiles, handing down to us a huge variety of fibres with different or not so different morphologies, found in excavations. To address that, we collected a large number of plant and animal fibres from all over Europe. Ancient Greek and Latin texts, as well as contemporary publications on textile finds were the sources that indicated the types of fibres to be collected. In total 23 different fibres were collected from 10 countries, namely cotton, flax, hemp, nettle, sparto, esparto, palm, papyrus, reed, club moss, lime tree bast, cultivated and several wild silk species, sea silk, various breeds of sheep wool, and goat, horse and deer hair. An interesting challenge was that not all fibres could be found processed and having been used to make a textile object, like the wild silks from the Mediterranean and certain plants (e.g. palm). Review of relevant literature and preliminary testing led to the development of specific methodologies for the removal of wild silk fibres from cocoons and the extraction of fibres from plants. The aim was that the end product, the fibres, would be clean enough so that their morphology would not be masked, and that the chemicals and the process of extraction would not affect their morphology.

The second factor that makes fibre identification challenging is that due to their organic nature, textile fibres are inherently extremely sensitive to the degradation mechanisms that take place during burial, which more often than not affect the fibres’ morphology to an unrecognisable degree. Therefore, we designed degradation experiments to simulate the conditions under which textiles have been preserved across Europe. The experiments were specifically designed to simulate deterioration in an excavation context, as this is typically manifested across Europe, namely mineralisation, carbonisation and biodeterioration (through burial in a high water content).

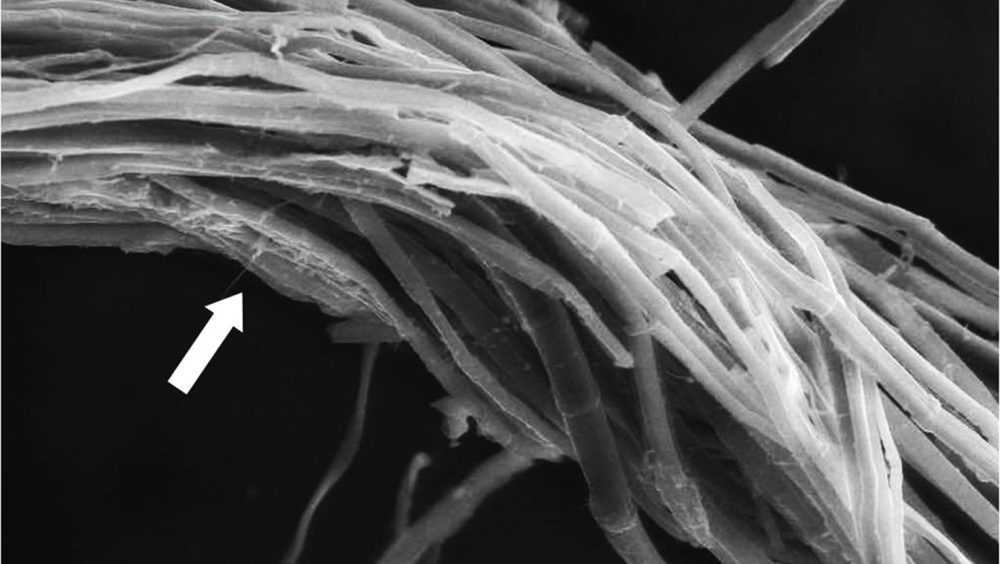

Samples of all fibres collected and experimented with were studied under optical and scanning electron microscopes at longitudinal views and cross-sections. Microscopic techniques for textile fibre identification have been researched in the past, since they are readily accessible, non-destructive to the samples and do not require highly sophisticated and costly equipment or highly specialised staff. However, microscopic fibre identification is not sufficiently explored, excluding the poor condition of the finds, usually including reference samples of well-preserved fibres produced by methods inapplicable to excavated ones. The results of this research, like fibre images, cross- sections and relevant references have been stored at an on-line - freely accessible database, where the end user can make correlations and fibre identification of their own finds.

FIBRANET investigated, synthesised old and new knowledge on Europe’s textile heritage by collecting and comparing information on textiles and fibres from ancient texts with current published case studies of excavated textiles, and produced data for textile fibres across Europe. It managed to: reveal information on fibres from Europe that had never been studied before; to demonstrate that the more often than not the poor condition of excavated finds can actually elucidate the study of the material when done systematically, because in the experiments carried out the different fibres were affected in such distinct ways that enhanced their identification; to provide new knowledge on the mechanisms of degradation of textiles in a burial context; and to create an on-line, Open Access database, a tool readily available to students and peer colleagues.