Learning about and from Coal Mining Boom Towns

Selm in Nord Rhein Westphalia, Germany and Workington in Cumberland, UK both share a coal mining heritage. Both were boom towns in their day and both suffered when employment collapsed with colliery closures. After many years of successful town-twinning, what can our young people find to compare and contrast in our heritage? What can be done along the way to value the past and secure a sustainable shared future?

One could say that coal mining in West Cumbria began in the 13th Century when the monastery of St Bees started extracting coal in the Whitehaven area. However, for Workington it started in the 16th Century with Henry Curwen, Lord of the Manor, who supplied coal to German copper miners in Keswick and also lime kilns and salt pans on the coast. As demand grew the Curwen family opened more pits, and by mid-17th Century coal was the town’s main export, 37 individual pits have been recorded! By 1700, the port had 160 ships engaged in the coal trade, largely with Ireland. This expansion led to a significant increase in the population of the town by the turn of the century, further enhanced by the establishment of iron foundries, as haematite was being mined nearby.

In July 1837 disaster struck Chapel Bank Colliery on the coast, when the roof collapsed and 27 miners, including 2 boys, and 28 horses drowned, as sea water inundated the mine and rendered Isabella, Union and Lady Pits unusable. The Curwen family made renewed attempts to find fresh sources of coal by sinking Jane Pit in 1843 followed by Annie Pit in 1864. In this period there was a great increase in rail construction for the transportation of coal and ore for local foundries and export, so the population continued to grow. Port expansion continued, but much of the coal was being used locally for iron and steelmaking. Jane Pit operated until it was closed in 1875. It is said that sea broke into the mine, tragically ‘entombing 100 miners’, but this is not reliably documented, perhaps 100 miners were put out of work? As a result of competition from foreign coal and oil, West Cumbria’s pits began to close in 1921, the last closure being 1986. The large castellated engine house and chimneys of Jane pit are the only above-ground evidence of Workington’s mining heritage, although the below-ground heritage has a habit of making itself know in more unfortunate ways!

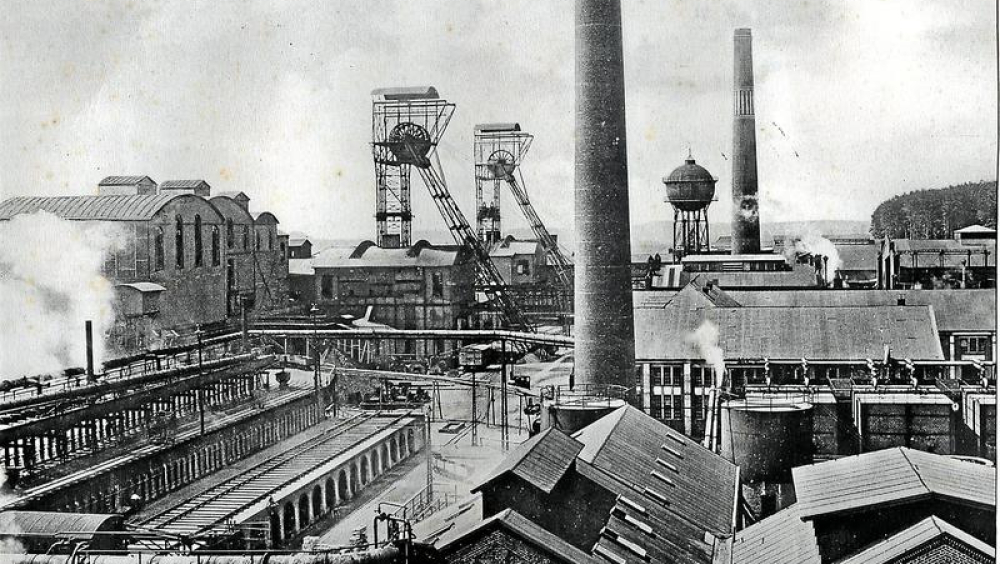

The small farming village of Selm had only 1,762 inhabitants in 1905, its neighbouring village of Bork was similar. At the beginning of the 20th century, test drillings were carried out in Selm and the surrounding area. Coal seams were found at a depth of 518 m to 1440 m and a mining volume of 397 million tons was calculated. In 1906, the ground-breaking ceremony began for the construction of Zeche Hermann colliery, in Selm-Beifang, comprising two shafts. In1908, a connection to the state railway was built from Bork. Since the Hermann colliery site also had extensive clay deposits, the colliery built its own brickworks. Bricks were needed to build the mine and facilities cost-effectively. In Selm-Beifang, beside the colliery, 518 houses were built with colliery bricks. The mine was the deepest in the Ruhr area at the time, making conditions difficult for miners who suffered in the heat. In 1911, a plant for producing sulphuric acid was built, and 80 coke ovens were added, with a plant for extracting the by-products. By 1914, there were 160 coke ovens, the colliery was a huge undertaking!

The 1914-18 war meant many miners were sent to the front, so prisoners of war, mostly Russian and French, local women, and children under 16 also worked at Hermann, to keep production going. The planned expansion of the mine never happened. In its best year, 1925, the Hermann colliery produced over 500,000 tons, but the slump on the international coal market affected Selm too.

In 1926, the mine administration applied for the mine to be closed, and the partial demolition of the above-ground facilities began. Selm had urbanised around the Hermann colliery, incorporating Selm-Beifang and Bork. Most of the miners became unemployed, so the lives of its 12,000 inhabitants became very difficult. Some miners obtained work at other mines around Dortmund, but the train from Dortmund only stopped at Selm and Bork, and most miners lived in Selm-Beifang. This meant travelling through the settlement to Selm station and then walking back 2 kilometers to get home at the end of a shift, and despite complaints, nothing changed. Hugo Barbian, a miner in Selm-Beifang settlement reported that the miners responded by pulling the emergency brake at Selm-Beifang so miners could alight or board the train there. Eventually the campaign was successful, and an official station was built. Today, the housing, the wage hall, stamp room and the canteen of Zeche Hermann still stand, renovated and used as HQ of Interhydraulik GmbH.

Now, in the 21st Century, both towns are taking a lead in caring for the environment and working towards sustainability. A family farm in Selm was the birthplace of an international recycling business, the Remondis Group. It now recovers raw materials from waste, develops innovative recycled products, offers alternative fuels and plays an important role in the water management sector supplying water and treating wastewater.

The Port of Workington, together with the Cumbrian Coast railway line, hopes to achieve the role of a key multi-modal hub for the region. Its development masterplan seeks to reduce road transport and support green industries and logistics. It is the base for the RWE offshore wind operations and maintenance facility servicing the Robin Rigg windfarm in the Solway Firth. With the development of Irish Sea leasing areas, it could provide installation, manufacture and maintenance for the offshore wind industry, and with the Prince of Wales deep-water dock of 1927, the port would support green energy developments relying on freight, such as Biomass or ‘Energy from Waste’ Power Stations. Close to Sellafield, it could provide logistics for the development of Small Modular Reactors, a future source of low-carbon electricity generation.

Young people in schools in Workington and Selm are keen to research their shared heritage and take a lead in bringing forward a bright zero-carbon future for both towns.

Research has been undertaken in both towns to capture the significance our coal-mining heritage, through archaeology, oral history and archival research. The EHD project will enable young people in Workington and Selm to undertake their own research and compare notes about what they find. By working with the English teacher in Selma Lagerlof Secondary School in Selm and the History Teacher at St Joseph’s RC Secondary School in Workington, there is the opportunity for increased cultural understanding and language learning, through conversations on Zoom and the sharing of resources, both with experts in the field and each other. The transition of the economies of both towns away from carbon-heavy extractive industry to aspirations towards zero-carbon living and biodiversity will further enhance the learning. The implications of reliance on a single-industry economy is clear through both our histories and the benefits of a diversity of skills and cultures and the diversification of economies can be life-enhancing, as we see through the success of our town twinning.