Lowestoft, Samuel Morton Peto and the Wider European World

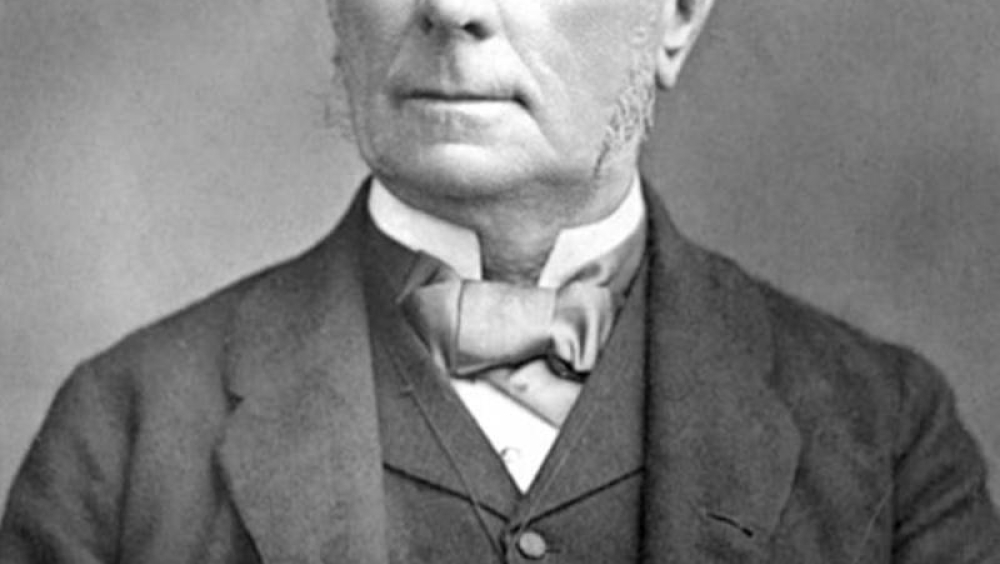

Denmark Road, Flensburgh Street and Tonning Street: three closely connected roads near the shopping-centre and railway station of the Suffolk coastal town of Lowestoft (the UK’s most easterly community). What possible connection can there be between this trio, the most southerly located of the Scandinavian countries and two towns in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein? The answer lies in the construction of railways by a man named Samuel Morton Peto (1809-89), who established his reputation as one of the leading builder-contractors in England (and in countries abroad) from the 1830s until the 1860s. He left an enduring mark on Lowestoft – often having been described as the ‘father’ of the modern town – but also on other places far removed, in terms of distance and culture.

This story, largely of fishing and maritime trade, wind-powered for centuries and later driven by steam engines and steel rails, is one which deserves to be more widely known – not only in the town of Lowestoft itself, but more widely across the whole of the United Kingdom and beyond. And, at the very heart of the crucial mid-19th century stage of the community’s overall development sits one dominant figure: that of Samuel Morton Peto.

Denmark Road, Flensburgh Street and Tonning Street: three closely connected roads near the shopping-centre and railway station of the Suffolk coastal town of Lowestoft (the UK’s most easterly community). What possible connection can there be between this trio, the most southerly located of the Scandinavian countries and two towns in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein? The answer lies in the construction of railways by a man named Samuel Morton Peto (1809-89), who established his reputation as one of the leading builder-contractors in England (and in countries abroad) from the 1830s until the 1860s. He left his mark on Lowestoft – often having been described as the ‘father’ of the modern town – but also on other places far removed, in terms of distance and culture.

During the 1830s and 40s, the family company (known as Grissell & Peto) built a number of notable London landmarks, the most famous probably being the Houses of Parliament and Nelson’s Column – as well as being involved in the construction of a new sewerage system for the city designed by Joseph Bazalgette. It was also during this part of his life that Peto became more and more drawn into railway engineering, producing an East Anglian line between Norwich and Great Yarmouth (1842-4) and another between Norwich and Lowestoft (1845-7). He seems to have developed a particular interest in Lowestoft itself, possibly as a result of knowing William Cubit, the man who had designed and supervised the construction of the town’s first harbour during the years 1827-30 (and who was himself also involved in building railways). And he even took up residence at a nearby countryside estate in the parish of Somerleyton, having its Jacobean hall remodelled in the popular Italianate style and a model Mock-Tudor village created out of nothing – complete with typical open green. He occupied this country-seat from 1844 to 1863 and made a considerable impact on the local area, both visually and socially. Peto was not merely a major industrial innovator; he was also a notable philanthropist and supporter of many Nonconformist Christian organisations, belonging to the Baptist denomination himself.

Returning to industrial matters, not only did he connect Lowestoft to the Midlands and the North of England by providing a rail-link to and from Norwich, he also made London and the South of the country accessible by creating a link with Ipswich, which opened in 1859. In tandem with this, he took the enfeebled harbour works in hand, improving both its function and potential with the creation of an outer-harbour extension and fish market, and with the establishment of the North European Steam Packet Co. Ltd. – thus introducing a cross-North Sea trade in livestock (mainly, horses and cattle) with the country of Denmark during the 1850s. And this is where the three street names assume significance because, at that time, Flensburg (Flensburgh being an Anglicised form of the name) and Tonning were still both part of Denmark – not Germany. The two names (together with that of the mother country) commemorated not only the newly established trading link with England, but the building of a railway by Peto which joined the Baltic town of Flensburg with the North Sea port of Tonning – the latter of which became the operating base for the new trading enterprise. Peto himself attended the opening of the line in October 1844.

It was also during the 1850s that he was involved in building a railway in Norway, between Christiania and Eidsvold (1851-4), and another in the Crimea – during the war waged there by a Franco-British-Sardinian-Turkish alliance against Russia. His company (Peto, Brassey & Betts) contracted to build a supply-line, at cost of materials and labour only, from Balaclava to Sebastopol (which was under siege) – a distance of thirty-nine miles. The work was completed in six months (February-July, 1855) and Peto made a baronet for his services. As well as carrying munitions and supplies from Balaclava to the front, the railway also served to convey hospital-trains with wounded soldiers on board away from the fighting. And this was not all. Another company associated with Peto, Lucas Brothers Ltd., made sectional wooden billets for the Crimean troops at its joinery works on the southern edge of Lowestoft’s inner harbour – at least, one of which served Florence Nightingale as a field-hospital during the hostilities.

Further links with the Crimean conflict are still to be found in Lowestoft, in the naming of certain roads in the same area of town as the three harking back to the cross-North Sea trading venture. Alma Road and Alma Street were named after the allied victory at Alma Heights in September 1854, while Raglan Street honoured the joint commander-in-chief, Fitzroy Somerset – the first Baron Raglan. There is also a fine, stained glass, memorial window in the Council Chamber within Lowestoft Town Hall, commemorating the main alliance between Britain and France. The building itself was designed (again in the Italianate style) by his locally-based architect, J.L. Clemence, and opened in 1860. Samuel Morton Peto presented the window (designed by his London architect, John Thomas) to the town – it having been previously displayed at the Paris Exhibition of May-September 1855, during which Peto made the acquaintance of the French monarch, Napoleon III. Five years later, the Emperor invited him to Paris, to discuss the construction of railways in France itself and also in the North African colony of Algeria.

There is so much to be said about Samuel Morton Peto, as both a national and international figure, that the words above barely scratch the surface. For instance, in 1850, he offered a guarantee of £50,000 to underwrite the Great Exhibition, staged the following year. And, yet, one further aspect of his contribution to the town of Lowestoft must not go unmentioned, either – and that is his creation of a model seaside resort immediately south of the town’s harbour, in the neighbouring parish of Kirkley. He and his uncle Henry, with whom he had started in the London building trade had gone to Great Yarmouth in August 1830 (eight to nine miles north of Lowestoft), to look at the possibility of creating a high-quality coastal holiday facility consisting of hotels and lodging-houses. Henry Peto died the following month and the project never materialised. But Peto obviously kept it in mind – and applied it to Lowestoft twenty years later, on a piece of coastal heathland which he had acquired.

Starting in 1847, he constructed a protective sea-wall carrying a generously wide esplanade and raised the Royal Hotel at its northern end (1848-9). This elegant promenade was fronted by thirty, large, paired villas - and behind these, with a road running between, he placed a terrace of fifty substantial lesser dwellings, known as Marine Parade (advertised, at the time, as “excellent second-rate houses”), and he ended by creating the monumental Wellington Terrace to the south of the villas (completed, 1856), with the same roadway as that passing Marine Parade separating the houses from a large, ornamental, communal garden – accessible to occupants only, by unlocking its gates.

The combination of everything that Samuel Morton Peto created in Lowestoft resulted in spectacular growth for the town, both physically and economically. The fishing industry, particularly – together with its many associated service activities – expanded rapidly. Not only in the long-established catching and curing of herrings, but also with the introduction of trawling in the southern parts of the North Sea – working productive grounds between Lowestoft itself and the Dutch coast, which had never been previously exploited. And, with the help of the railway bringing in people from outside the town’s immediate area, the summer holiday industry began to make an impact in the newly created resort to the south of the harbour. In 1841, the town’s population stood at 4,238 – rising to 6,781 ten years later. By 1871, it had reached 13,623 and 19,150 in 1891. In August 1885, Lowestoft was awarded borough status by royal charter, which gave it the self-governing structure of a mayor and elected councillors, and its growth continued – reaching 37,886 by 1911, which made it Suffolk’s second largest town after Ipswich. It retains that position today, with the census return for 2011 giving a total of 71,495 people for its total urban area (which includes smaller places it has absorbed) – and with a count of 48,895 for the original parish itself. The foundation blocks for this notable expansion, over the years, can be directly attributed to the innovations introduced by Samuel Morton Peto during the middle of the 19th century.

But the story must not be allowed to end there. Long before Peto arrived on the scene, Lowestoft had been connected with the continent of Europe, for centuries, in a number of different ways. From the first half of the 14th century onwards, its growing involvement in commercial fishing and maritime trade brought it into contact with countries from the other side of the North Sea and from further afield as well. The town had no harbour as such, but it was favoured with an inshore anchorage between the offshore sandbanks and its area of beach which was sufficient to provide safe haven for as many as 500 vessels at low tide – this particular number being mentioned in an official survey of coastal defences carried out in May 1545. Not only did this facility (with the use of ferry-boats) allow the loading and offloading of ships engaged in fishing and the carriage of widely varying cargoes, it also provided a place of refuge for passing traffic in stormy weather – to say nothing of its being an area, also, where vessels could lay in and carry out trading in goods which should have paid customs duties in the nearby port of Great Yarmouth. It also enabled vessels to anchor up and take on supplies of basic foodstuffs, ale, beer and fresh water, if needed.

Records of the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries show regular contact between the town of Lowestoft and shipping from Scotland, France, Holland, Flanders and German states along the Baltic. The goods mentioned, in various contexts, include wine, wool and woollen cloth, linen, cured fish, grain, malt, animal hides and leather, timber, hemp and cordage. The autumn herring season in Lowestoft’s sector of the North Sea was one of the town’s main sources of wealth, with the bulk of the catches being heavily salted and smoked (with the gut left in) to form what were known as red herrings, because of their bronze colour after being cured. This foodstuff had long-keeping qualities and its imperishable nature made it popular. Large quantities were shipped to other parts of England, as well as to the continent of Europe – a favourite destination, here, being the Italian port known at the time as Leghorn (now, Livorno). In a completely different context, during the 15th century, the port of Venice traded in a coarse linen cloth known as loesti, which had its origins in the hemp fibre grown and woven locally in the Lowestoft area and which found its way to the Italian city via London.

Another part of the town’s late medieval fishing enterprise, which developed during the early-mid 15th century and lasted until into the first half of the 18th, was the annual springtime voyage to Faeroe and Iceland, to hand-line for cod and ling. The fish were decapitated, gutted, salted down and dried on board, before returning home and then being re-processed in various ways, prior to use. Again, as with red herrings, they formed an item of commerce with other parts of England and, in some cases, with foreign nations also. The other main maritime link which Lowestoft had with the mainland of Europe was the Baltic trade which developed between it and Livonia (now Estonia and Latvia) during the 16th and 17th centuries, with cured fish, malt and other foodstuffs going outwards and softwood timber, hemp, cordage pitch and pig-iron being brought in on the return journey. These marine stores, as they were called, reflect the growth in Lowestoft’s fishing and trading capacity, leading to it needing more and more specialist materials to build and maintain shipping. The main point of contact in this traffic was the port of Riga – and there was even a Lowestoft trading vessel which bore that very name during the second half of the 17th century.

However, it wasn’t just the traffic in goods which the town experienced. During the mid-late 15th century particularly, the town saw an influx of immigrants from Holland, Flanders and northern France. Fifty-five people in all are recorded in official records of the time (six of them women), most of them named, but with some of them having the forename only and their trade serving as a surname. All of them were mainly of the skilled artisan class, with occupations such as brewer, shoemaker, cooper, tailor and skinner (animal hides) plain to see. A few of them are detectable as having settled in Lowestoft, but the majority of them obviously moved off elsewhere after coming to a new land. It is difficult to be specific regarding what circumstances caused this migration, but there is no such doubt regarding what happened during the early 1570s. Between 1571 and 1574, the Lowestoft parish registers show that at least twelve Dutch Protestant families were based in the town, having fled persecution in their homeland imposed by the Spanish occupiers. Nearly all of them moved on somewhere else, after their short period of residency – quite possibly to Norwich, which had a long-established “strangers” element (to use the term of the time) in its own native population.

What else is there to be said, when so much more could be added? We must, almost inevitably, return to commercial fishing for the final word. As a result of Samuel Morton Peto’s innovations and improvements in the town he had adopted, the local fishing industry expanded noticeably and quickly (as was referred to earlier). Among the European links established, during the second half of the 19th century, was the importation of ice from the Norwegian fjords to help with the preservation of catches on board ship and in assisting with curative processes onshore. This was because the usual supplies harvested from local marshes and lakes were not sufficient to meet the demand caused by the increase in catches.

The herring industry, particularly, expanded enormously at this time, as a result of increasing numbers of Scottish fisherman and shore-workers coming down each autumn to take part in the autumn season. There were, literally, many thousands of them each year by about 1900 and their speciality was the famous Scotch cure – fish which had the gills and long gut removed, before being salted and packed in layers, sardine-fashion, into barrels for shipment to (mainly) Germany and Russia. It was a lucrative trade – as was the other well known-one of the time (to Germany) which began in the 1890s and lasted until the outbreak of World War II. This had the name of Klondyke attached to it, in reference to the Canadian gold-rush in the Yukon, and it consisted of the exportation to Altona of ungutted fresh herrings, salted and iced down in large wooden boxes, for final processing in Germany itself.

This story, largely of fishing and maritime trade, wind-powered for centuries and later driven by steam engines and steel rails, is one which deserves to be more widely known – not only in the town of Lowestoft itself, but more widely across the whole of the United Kingdom. And, at the very heart of the crucial mid-19th century stage of the community’s overall development sits one dominant figure: that of Samuel Morton Peto.

Lowestoft, the most Easterly settlement in the UK, has always looked beyond the boundaries of the United Kingdom for its existence. Throughout the ages, it has engaged in trade, immigration and cooperation with its European neighbours and beyond, through their shared border - the North Sea. The work and investment of Samuel Morton Peto into the town and surrounding area has helped to consolidate and connect the town more successfully, both with the rest of the United Kingdom but also to allow better communication between Europe and the UK. Peto's work within Europe has also helped to indirectly connect Lowestoft trade with the conflict at Crimea and beyond.

Lowestoft celebrates it's European connections by participating in the European twinning scheme, being twinned with the town of Plaisir in France.