The Unexpected Journey

Galicia’s Call: Hosting the ICLCM Conference in a Land of Poets

When the International Committee for Literary and Composer’s Museums (ICLCM) faced an unexpected crisis, Galicia answered. As the first Galician President of ACAMFE, I was entrusted with organizing the annual conference in record time after Norway’s cancellation due to travel restrictions for Russian members. This was more than a logistical challenge—it was a chance to showcase Galicia’s rich literary heritage on a European stage.

From Santiago de Compostela, final stop of the Camino, to the poetic homes of Rosalía de Castro, Nobel Laureate Camilo José Cela, and Castelao, we led delegates through a journey where literature, music, and history intertwine. Medieval troubadour traditions, female minstrels (soldadeiras), and the deep connection between poetry and song were at the heart of the experience.

The highlight came in the Courel Mountains, home of my father, poet Uxío Novoneyra. In this UNESCO Geopark, surrounded by ancient forests and echoes of his verses, the conference found its soul. Delegates from across Europe realized that literature is not just in books but woven into landscapes and communities.

Galicia, often seen as peripheral, proved itself a central hub of European literary heritage. This was not just a conference—it was a testament to cultural resilience, transnational dialogue, and the enduring power of the written word.

I had barely settled into my new role as President of ACAMFE, the Iberic network of literary houses, museums, and foundations when the call came. A month into my tenure, an urgent request landed in my inbox. The International Committee for Literary and Composer’s Museums (ICLCM) was in distress. Their annual conference, originally planned for Norway, had been abruptly derailed—Norway’s policies barred Russian citizens from entry, and many members of the ICLCM hailed from Russia. An alternative had to be found, and fast. Would I, a newly elected president and the first Galician to hold the office in ACAMFE’s 30-year history, be willing to take on the challenge?

Could Galicia, the nation of 3,000 poets, welcome the ICLCM?

The weight of the decision pressed on me. This was more than a logistical undertaking; it was a historic moment. Galicia had never hosted the ICLCM before. Did they even know what Galicia truly was? Our land, famous for its poetry and its minoritized language, the father of modern Portuguese, the southernmost Celtic nation in Europe, was about to step onto the world stage of literary heritage. With determination and no small measure of anxiety, I said yes. And so, the race began.

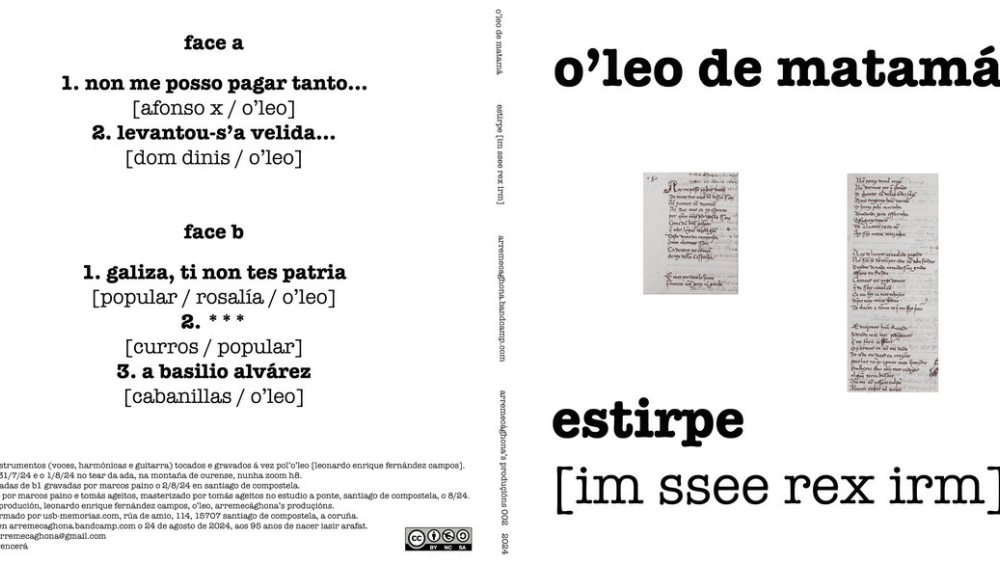

Santiago de Compostela, city of pilgrims, troubadours, and now poets, would be our first host. As delegates arrived, I watched them marvel at the stone-clad streets, the towering cathedral, the whispers of centuries past embedded in the air. Here, in the Obradoiro Square, where medieval troubadours once sang, the conference was inaugurated. Representatives from Galician cultural institutions extended their greetings, but it was ICLCM President Adriano Rigoli who set the tone: this would be a conference about literature’s deep entwinement with music, dedicated to the memory of Uxío Novoneyra, my father, the wolf poet of the mountains, who passed 25 years ago.

The first sessions delved into the roots of Galician-Portuguese medieval literature in Raxoi Palace, the Santiago City Palace, located right in front of the Cathedral of Santiago, the final destination of the Camino. Inside one of the most beautiful libraries in the entire Spanish state—the Library of the Galician Cultural Council, Galicia’s foremost institution for the preservation of culture and language—attendees explored the golden medieval age when King Alfonso X the Wise was the first of the Galician-Portuguese troubadours, when poets wove music into poetry, when María Balteira, both troubadour and dancer, sang and danced her verses, and when the first songs of our identity took shape. I watched the faces of the attendees—scholars, curators, writers—as they absorbed the living continuity of Galicia’s literary past. As Novoneyra wrote in his masterpiece The Uplands:

I speak with you, King Alfonso Esquío

and Torneol

But Meogo and Mendiño, you who carry the flower

With you, King Don Dinis of Portugal, Per Amigo

Roy Fernández of Santiago, Martín Codax of Vigo

With you, Galicians of muffled voices, Galicians of crystal

Joan Airas, Airas Nunes, Bernal de Bonaval

Martín de Padrocelos, near where I was born

Esteban Coello – the beautiful one who spins and sings gently

Joan Zorro, the one of the dance and the boats in Lisbon

Cerceo Bolseiro of Armea, of Guillade, of Ambroa

And of A Ponte, Lourenzo Martín, Moxa Eanes

of O Cotón

Roy Paez, Soares Lopes, Lopo Lías, and so many more

who are

And among all the female minstrels, only you, María Balteira

Beautiful with the dice, supple in the dance, the first.

I am a troubadour of thought

One should not be called a troubadour

A troubadour who sings just to sing

Without suffering such sorrow

That he could not remain silent without pain.

And it is not necessary to say

For whom this song is meant.

From Compostela, the final Campus Stellae, the destination of all the Ways of Saint James, we followed the path of the written word across the land.

In Padrón, we paid homage to Rosalía de Castro, the mother of the Galician people, an ancient global diaspora and modern nation without a state that proudly holds a Galician female poet as its icon. Standing in her home-turned-museum, we listened to her verses, still alive with longing and defiance, echoing through the stone walls. In the evening, the folkloric singer Su Garrido performed, bringing Rosalía’s words to life in song. Delegates, some unfamiliar with Galician, sat spellbound, transported by the melody alone.

The next day, we honored another giant of literature, Nobel Laureate Camilo José Cela. In his house-museum, we traced the corridors of his creative mind. We then traveled to the sea village of Rianxo, where three literary titans once walked: Castelao, Manuel Antonio, and Rafael Dieste. Castelao, a writer and politician, remains a beacon for Galicians—his dreams of cultural dignity were forged in exile, and we stood at his birthplace on the cusp of his 75th anniversary of passing.

Manuel Antonio, the poet of the sea, was felt most strongly when we visited his home. His verses, written with the rhythm of ocean waves, reminded us of Galicia’s deep relationship with nature and its lyrical inspiration.

Then, to Lugo, where history and literature entwine. This wild inland Galician province, larger than Ireland and sparsely populated, is home to some of the finest poets of this Roman Finisterrae. We traced the footsteps of medieval troubadours along the UNESCO-listed Roman walls, stopping at the statue of Ánxel Fole for a floral offering. The literary route of Lugo was more than a tour; it was a bridge between eras, guided by the young poet and journalist Nieves Neira.

But the true climax came when we journeyed into the Courel Mountains—the wild, untamed heart of Galicia, a UNESCO Geopark with settlements over 500 million years old, filled with chestnut forests, wolves, and bears. The mountains of Uxío Novoneyra, my father’s and my mountains, where poetry is etched into the very rocks and trees, and where the memory of mountainous peasants, cowboys of horses and bulls, still lingers. Here, in one of Europe’s most isolated, depopulated, and wild mountain ranges—scorched by the second-largest wildfire in Spain’s history in 2022—we walked through forests once traversed by the poet himself. Delegates from across the world found themselves immersed in a different time, a different rhythm, as they stood in Novoneyra’s literary sanctuary.

As the conference neared its end, we gathered at the Uxío Novoneyra Foundation, the poet’s birthplace and final resting place, the only poet’s grave in Spain within his own home. The tombstone reads in stone: The dreams and the birds say: Death is not true. The air was thick with the scent of damp leaves and pine, and the voices of the participants rang with emotion when I recited The Travel Poem in front of his grave:

Let us go, and in us return all those who were...

From all the ships, horses, and carts that depart, a song of permanence flows...

There are journeys that do not even need the sea.

When the final remarks were made, a senior member of the ICLCM approached me.

“This,” he said, eyes gleaming, “has been the finest conference we’ve attended in years.”

This was not merely an event; it was a statement. A declaration that my Galicia’s literature and language are not relics of the past but living, breathing forces. That literature is not confined to books but is woven into landscapes, into voices, into the soul of a people.

As the last farewells were exchanged and the delegates departed, I stood in the Courel twilight, knowing that Galicia had not just hosted a conference. It had carved itself into the memory of those who came, as poetry carves itself into the heart.

And I, once hesitant, once uncertain, now knew the answer to the call that had come a month before.

Galicia had answered. And it had sung.

Based on the call guidelines, our story about hosting the 2024 ICLCM Conference in Galicia aligns with key European heritage principles by demonstrating cross-border cooperation, cultural exchange, and the protection of linguistic diversity. Here’s a response addressing its European impact:

The ICLCM Conference in Galicia exemplifies how heritage can serve as a bridge between European peoples and identities, fostering cultural dialogue and cross-border cooperation. By welcomingliterary heritage managers from across Europe after the event was relocated from Norway, Galicia reaffirmed its position within the shared cultural history of Europe, particularly through its deep-rooted literary and pilgrimage traditions.

At a European level, the conference highlighted:

- European literary heritage: Galicia, as the birthplace of the Galician-Portuguese troubadour tradition, showcased its contribution to European medieval poetry and the Romance languages. By tracing the cultural footprint of figures like Alfonso X, Martín Codax, and Rosalía de Castro, we connected Galicia’s literary past with European literary movements.

- Cultural resilience and linguistic diversity: Galicia, with its minoritized Galician language protected by European Card of Minoritary and regional lenguages, demonstrated the vitality of linguistic heritage as a cornerstone of European identity, echoing the values of the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention on Cultural Heritage.

- Collaboration across borders: Hosting ICLCM members from multiple European countries, including those affected by geopolitical restrictions, reinforced the role of heritage as a neutral space for cultural diplomacy and academic exchange.

The conference also directly aligned with EHD priorities by promoting:

✔ Education – Through literary routes and house-museums visits in Santiago de Compostela, Padrón, Lugo, and Courel, the event deepened awareness of European literature’s interconnectedness.

✔ Participation and engagement – By involving local communities, musicians, and young literary heritage managers, the project fostered a living, participatory approach to heritage.

✔ Environmental sustainability – The journey through the Courel Mountains (UNESCO Geopark and Reserve of Biosphere) emphasized the intrinsic link between natural and cultural heritage, highlighting the impact of climate change on literary landscapes.

By bringing together European literary heritage managers, and local communities, the ICLCM Conference in Galicia set an example of good practices for other European cultural projects. It reaffirmed literary heritage as a living force—one that is not confined to books but embedded in the landscapes, languages, and shared histories of Europe.