Under Suspicion

Country

United Kingdom - England

Organization name

Buxton Crescent Heritage Trust

Storyteller

Stephen

E-Mail: sowen@bchtrust.org

Overview

2023 marks the 450th anniversary of the first visit of Mary Queen of Scots to Buxton, Derbyshire in the Peak District of England, to take its miraculous, healing thermal waters. At the time Buxton was little more than a hamlet of maybe 300 people. Once a Queen Consort of France, Mary inherited the Scottish throne aged just six days old. The Protestant and Catholic tensions throughout Europe during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries meant that the Catholic Mary was imprisoned by her Protestant cousin, Queen Elizabeth I, for 19 years until her execution in 1587. After petitioning Elizabeth to come to Buxton to take the waters, Mary gained relief from her ailments, visiting at least eight times in eleven years. Still a divisive figure today, we tell the story of her visits and the impact she had on Buxton, now a thriving spa town, hidden away in the remote English countryside.

The year is 1573, William Cecil, Lord Burghley and chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I, writes to George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury:

“Her Majesty is pleased, that if your Lordship shall think you may with peril conduct the Queen of Scots to the well of Buckston, according to her most earnest desire, your Lordship shall so do…”

Mary, Queen of Scots, suffering from poor health, petitioned her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I, to come to the small village of Buxton in the Peak District of Derbyshire, England to take its miraculous, healing, thermal waters. A book, written in 1572 by a Dr Jones of Derby, entitled ‘The Benefit of the Auncient Bathes of Buckstones, which Cureth most grievous Sickness’, was said to bring the waters into ‘a high degree of vogue’.

“…if in very deed her sickness were to be relieved thereby, her Majesty could not in honour deny her to have their natural remedy thereof…”

However, Elizabeth was concerned for her security in the remote, exposed landscape.

“…her Majesty was very unwilling that she should go there, imagining that her desire was either to be the more seen of strangers resorting there, or for your achieving of some further enterprise to escape…”

Under the custody of George Talbot since 1569, following her escape from Scotland in 1568, Mary was confined to his properties, all located in the interior of England, halfway between Scotland and London and distant from the sea. There were no considerable or secure buildings in Buxton at this time, nor any which could house her entourage - her ladies, cooks and gaolers - so, the Earl erected “new and goodly buildings”, a four-storey, fortified tower, to provide Mary with secure accommodation and private access to the baths. The principal building was “the first convenient house for the reception of visitors”, “a fine mansion”. It was the largest building in Buxton at this time and has had many names over the years: Hall House, Talbot Tower, Buxton Hall, New Hall, Auld Hall and more recently, the Old Hall Hotel.

Thought to have been suffering from rheumatism, Mary wrote of the water,

“It is incredible how it has relaxed the tension of the nerves, and relieved my body of the dropsical humours with which, in consequence of my debility, it has been charged.”

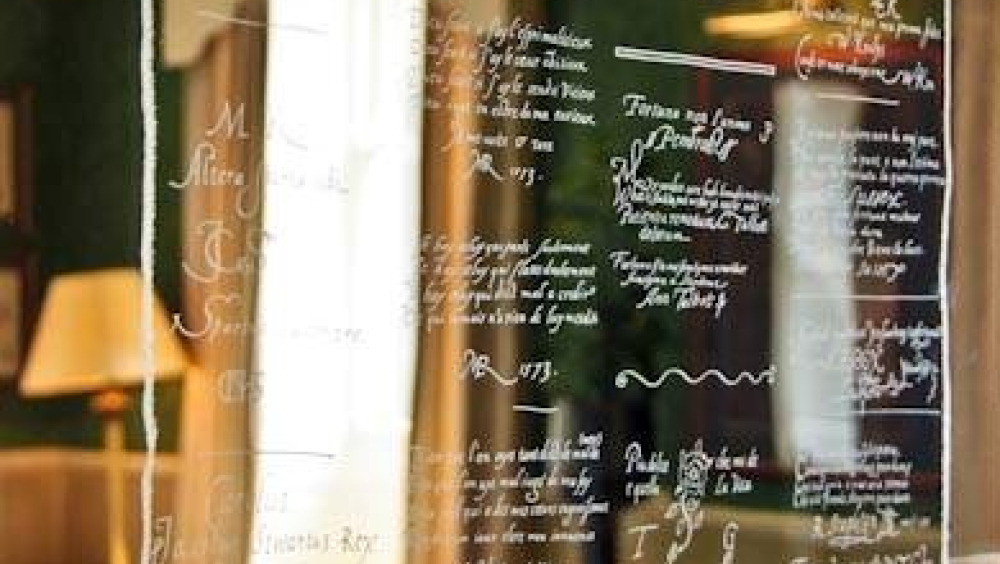

We know Mary came to Buxton at least eight times between 1573 and 1584 because she was one of the town’s first known graffiti artists. There was a culture of scratching into windows with diamond rings and Mary, along with much of the Elizabethan court, and notorious Catholic-hunter Richard Topcliffe, left their marks. 16 of the 39 examples of window writing are thought to have been written by Mary, reproductions of which were restored to the Old Hall in 2012.

On her final visit, in 1584, Mary inscribed, in Latin, on one of the window panes of Room 26,

“Buxton, who warm waters have made thy name famous, perchance I shall visit thee no more – Farewell”.

This proved prophetic as the political climate was changing against her and accusations of treason took hold. She was soon removed from the custody of the Earl and, on 8th February 1587, Mary was executed at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire.

The building of the tower put Buxton on the map, literally. In the first pictorial maps of Derbyshire in the mid-16th Century, the village was just one-of-many tiny settlements in the north-western corner of the county. Later maps, such as by John Speed in 1610, singled-out the village from all others with a picture of the Hall in the lower right corner.

The original tower still stands in the centre of the hotel today, with its low doors, thick walls, small windows and plainer architecture: this was confirmed in 1990 by the Royal Commission on the Historic Monuments of England. Although there are no contemporaneous records of any inns in Buxton until the ‘Auld Hall’ in 1573, where it stands is thought to mark the spot with the longest continuous provision of accommodation in the country, with the stone tower replacing a structure offering only the most basic hospitality to travellers.

The Hall, following a fire in 1670, was renovated and extended by the 3rd Earl of Devonshire. In 1697, it was still the “largest house in the place tho' not very good” according to traveller, Ceilia Fiennes. “the beer they allow at the meals is so bad that very little can be drank.”

The current fronticepiece of the Hall dates from 1726 and it was extended many times along with improvements to the adjoining bath houses. Refurbished in 1980, it is now run by Ensana, a central European chain of spas alongside the neighbouring Crescent Hotel and spa.

The spa town of Buxton has much to thank Mary for. Without the building of the Hall in the Elizabethan era to house her, and without the interest brought by her visits, the waters may not have become so well-known: they may not have attracted the attentions of curious 18th Century physicians; the 5th Duke of Devonshire may not have been persuaded by them to build his Georgian spa; the Victorians may not have developed the town into a medical health resort; the railways may not have arrived in 1863, galvanising its transformation into an inland holiday destination; and the Opera House, added in 1903, and which represents the town’s identity today as an arts festival town, may never have been built.

Over the past few years, Buxton has celebrated its Georgian heritage, following the restoration of the Grade I-listed Crescent and re-opening of the health spa, but in 2023, on the 450th anniversary of the first visit of Mary Queen of Scots to the town, we celebrate its Elizabethan history.

You can still enjoy the hospitality of the ‘Auld Hall’, even staying in Mary’s Bower, her bed-chamber, and you can also be received by the Queen, herself; well, a costumed character guide on Discover Buxton Tour’s heritage experience.

European Dimension

Our story embraces three European countries – Scotland, France and England.

Marie Stuart (MQOS) was born in 1542 to the King of Scotland, James V, and his French second wife, Mary of Guise. She was six-days old when she inherited the Scottish throne. There were two claims to the regency: one Catholic and one Protestant.

Mary was born into the tensions between Catholics and Protestants whose conflicts, the Wars of Reformation, would come to characterise European Christendom during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Through telling her story, we can open up the events of this period.

Her story can also demonstrate the life, and political use, of noble women during this time: aged 1, she was pledged to marry King Henry VIII’s son, Edward, to strengthen the Union of England and Scotland. Aged 5, she was sent to France, promised to the French Dauphin, Francis, to renew the ‘Auld Alliance’. She grew up in the French Court, becoming Queen Consort of France in 1559 but, following the death of Francis, she returned to Scotland in 1561 to live a life of accusation and imprisonment.

The use of thermal waters for the restoration of health also has a European heritage in terms of the ‘continental spa’ and her visits to Buxton provide us with a way to explore the world of 16th Century science, the Scientific Revolution and the beginnings of the European Age of Enlightenment.

Letters written by Mary, recently found in the French National Library and deciphered, made national news, demonstrating she still has a modern appeal and is a relevant historical figure through which to educate and inspire: the Tudors feature in Key Stages 3, 4 and 5 of our national curriculum and Glasgow University has just completed a five-year research project exploring her ‘cultural afterlife’.