Wharf Wide Web; how the waterways of England connected to the Globe

Clip clop, clip, clop.. a tired horse plods forward beneath a glittering sky. An equally tired woman plods behind him, one hand resting on the taught rope joining the weary animal and the heavily laden boat it pulls, the other clasps the shawl around her shoulders.

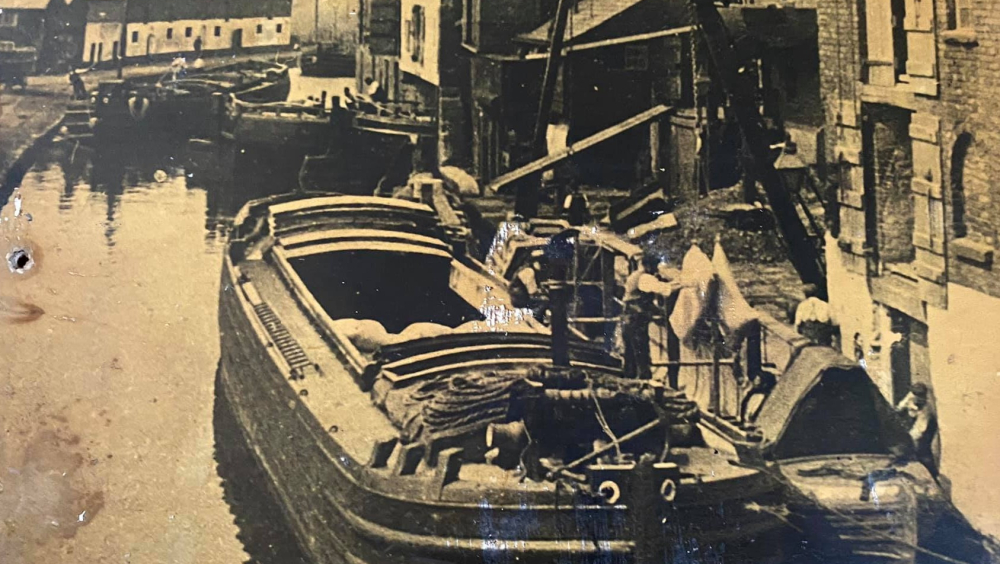

Step aside viewer, let them walk past. Look to the boat. The black hull is almost indistinguishable from the dark of the night. The top plank of the bow gleams white, reflecting our helpful moon, and colourful diamonds end the streak at the boats shoulder. Her cargo, exposed to the night, is mixed; alcohol from Portugal and France, timber from Norway, wool from Belgium, sugar from Jamaica, tobacco from America.

Once the waterways of Britain were the superhighway of trade and commerce; the vital link between our country and the rest of the world, and powered by the blood, sweat and tears of thousands of unsung heroes.

No quaint holiday in the bucolic countryside is this, but a tale of slavery, of war, of immigration and emigration, of real people and of tiny details that shape the course of history.

The small cabin to the stern of the boat glimmers in the light. Bold colours announce the owners name. These colours will not fade easily, for the signwriter used the most expensive pigments for this, shipped in from the same far off places as the cargo.

A painted scene, clearly not from these shores, adorns the side. Little sailboats drift on a calm sea under the watchful eyes of inescapably, if indeterminately, European castle.

The top plank of the stern, like the bow, is painted. The boats name is declared here, “Baltic”. She is named for the Baltic timber trade made her owner a wealthy man, and caused her, and her sisters, construction.

Look now at the master of the boat as he leans on the roof of the cabin, the painted tiller tucked under his arm. He is not her owner. The owner in fact has no idea who the boatman is, beyond a name in an account book.

He is stood in the open doorway of the cabin, and you can see that the doors themselves and the panel he leans on are covered in bright painted flowers. You could be forgiven for calling them crude, for they are not elegant still-life. In fact they are far from it but, stylised they may be, they are full of life.

Today most people when they imagine canals, they picture slow boats meandering lazily through the countryside under the command of rosy-cheeked water gypsies who little concern themselves with the world outside of their cabin. But that is a fairytale. The real story is gritty, sometimes dark and tragic, sometimes triumphant and full of hope.

Beginning in the 1700s, reliance on inland water transport grew as tensions and wars with Europe made it increasingly unsafe to rely on open seas.

As the tendrils of water expanded over the English countryside, men of power and riches pushed the strands of commerce and industry over the seas and into Europe and the rest of the globe, but most of those men never pushed anything heavier than a pen, or saw anything change but their bank balance and their home décor.

One little village in England was right in the thick of the real story though. First working in 1770, at Preston Brook painted narrowboats shuttled to and fro from across the country to swap cargoes with dour coastal flats, who in turn swapped with mighty tallships at Liverpool. Men, and women, heaved cargoes in and out of hulls and swapped news of far off places and ideas from different lands. Art styles, music, stories, superstations; all the ingredients of intangible cultural heritage were poured into a pot at Preston Brook and shipped off on boats, big and small, as a hidden cargo to subtly shape the canal people and townfolk alike.

But the shadow side of this access and control was just as far reaching. For more than 30 years, Preston Brook handled almost all of the cargos to and from Liverpool attached to the slave trade, including some of the humans themselves when they passed through with their “owners”.

Weapons, ammunition and even soldiers themselves were loaded and unloaded regularly at Preston Brook, heading to Ireland, France, and the Americas as war dictated. Some of Preston Brook, both boaters and wharfmen, were lured to serve in the Napoleonic wars, with those who returned bringing back nightmares in trade of limbs.

Many bruised and broken hearts passed through the wharf with the emigration from the English depression, immigration from the Irish famine and even refugees from the French revolution.

The story of the wharf and the waterways is not just the story of the canal people of England, it is the story of soldiers and sailors, wives and widows, rich men and poor from all across Europe. It is the story of how the smallest choice can change the course of country, and of how the voices of those long past can still be heard.

The stories of the wharf and the waterways can teach us many things, but the key moral to each one is that no one is too small to make a difference and everyone is truly connected. Heatherfield Heritage wants to reclaim these lost stories, and make all the cultures, skills and heritage they link us to accessible for everyone, regardless of their background.

The inland waterways were a vital link to Europe both in terms of the physical cargoes they carried and the ramifications thereof.

The people who worked the waterways in particular had a unique perspective of Anglo-European events and relations in comparison to the rest of the country, as events across Europe and the rest of the globe directly affected trade on the waterways; and at ports and wharves there was an inescapable meeting with people from different countries and cultures, with both sides leaving with new ideas.

Although the exact ‘what’, ‘when’ and ‘how’ are highly debated, it is undeniable that traditional canal art itself was influenced by European art styles, and there are interesting crossovers in cultural behaviors between watermen and their European counterparts.