Sea People: memories for future

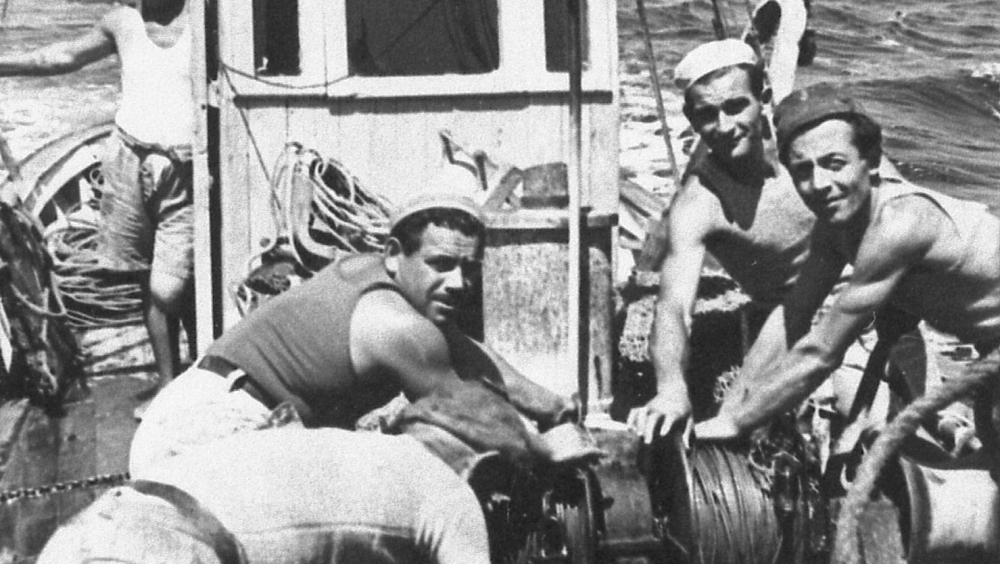

Beginning in the 1920s, the passage from the lugsail fishing boats to the motorized propulsion system started radically to change the complex interdependence between the human and the sea in the coastal towns of the Italian Middle-Adriatic Sea. For centuries, fishermen had been confronted with the vagaries of the sea, and had developed sophisticated practical knowledge and magical-religious beliefs to reckon with the perils of the marine streams, tornadoes and storms. The 1950s marked a real watershed in the centuries-old history of the traditional seamanship in Central Italy as the motorboats, in tandem with the new technological devices for navigation, enabled fishermen to control the radical unpredictability that had long marked their everyday worlds and imaginations. On the other hand, the massive exploitation of the marine resources, made possible by these technological developments, has triggered unprecedented transformations. Because of the increasing degradation of the seafloors, the restrictions imposed by the European Community (e.g. the ban on the use of drift nets in 1997) to ensure viable fisheries have posed new challenges for the fishing communities, who have faced seasons of crisis and now have to envision sustainable futures. The Museo la Regina of Municipality of Cattolica (Rimini) has dedicated an entire section to the local seamanship and, in 2002, realized the documentary feature ‘Living Archives of the Sea’ (Archivi viventi del mare, Ceschi) based on 14 interviews with old fishermen. However, the history of the motorization of the traditional fisheries, embodied in the memories of a generation of fishermen that is slowly disappearing, with its socioeconomic and ecological implications, still needs to be fully recovered. Sea people’s personal memories are an integral part of an intangible heritage, with deep transregional dimensions, which has the potential to trigger inter-generational dialogue, to raise public awareness of historical roots of the present and to foster the imagination of sustainable futures.

“The marine engine is both joy and pain, like women, as people used to say at that time” says Mario Tamburini, a fisherman born in Cattolica in 1911. “Between sail and engine there is a big difference: with the sail, when there was dead calm (bonaccia), the boat stayed still and we could not even catch enough fish for eating”, explains Vittorio Ercoles, born in 1920, and continues, “the first engines got to 24-25 hoursepower engines, so we had to keep the sails, as when there wasn’t wind we could hardly fish. Having the sails, when there was a bit of wind, we empowered the engine with the use of the sails”. “Toward the 1930s, more powerful marine engines began to be installed and this improved our activity, but they were still too small”, explains Colombo Bontempi, born in 1915. “In the latest years, we reached real desperation. The others [motorized boats] named us, the sailing boats, the squadron of the unluckies (squadriglia del baloc), because we didn’t fish anything”, remembers Marcello Prioli, born in 1921, and adds, “When there was dead calm (bonaccia), the motorboats fished a bit, in spite of the engine’s limitations, whereas us, we were unable to tow the net. When there was a seastorm, then, we had to go back”. The owners of the motorized boats were mainly ‘land people’, as the fisherman call those people who were not engaged in the handling, working and navigating a ship. Sea people, indeed, inhabited a life-world - with its distictive traditions, knowledge and beliefs - which was at once set apart from the broader community, by which they were marginalized and depreciated, and an integral part of it. “Fishermen didn’t have money, wholesalers bought the marine engine … they supported the costs and said ‘I will sell the fish and keep a percentage of the gain’, but they were always the bosses” says Prioli to emphasize the divide between the “sea people” and the “land people”. “Now, when they sailed the sea, fishing boats are like hotels, they have all imaginable technological devices, starting from radar, sonar, automatic pilot, radiators, they cook pasta two times a day” concludes Piero Lucarelli, former president of the Fisherman’s House, fishermen’s cooperative established in 1923. These voices belong to a generation of fishermen in the coastal towns of the Italian Middle-Adriatic Sea who experienced the passage from the lugsail fishing boats to the motorized propulsion system between the 1920s and the 1950s. Taken together, their personal memories compose the multivocal history of the deep transformations that affected traditional seamanship – conceived both as the nautical arts and the sea people’s everyday practices and religious imaginations - in the XX century. For centuries, indeed, fishermen in the Adriatic Sea, and in the Mediterranean Sea more broadly, had been confronted with the vagaries of the sea and the weather, and had developed sophisticated practical knowledge (for navigation and orientation) and magical-religious beliefs to reckon with the perils of the marine streams, the tornadoes and the winds. In particular, the 1950s marked a real watershed in the centuries-old history of the traditional seamanship in Central Italy as the motorization of the fishing boats, in tandem with the new technological devices for navigation, enabled fishermen to exert control on the radical unpredictability that had long marked the complex interdependence between human and the sea. On the other hand, the massive exploitation of the marine resources, made possible by these technological developments, has triggered unprecedented societal and environmental transformations. Because of the increasing degradation of the seafloors, the restrictions imposed by the European Community (e.g. the ban on the use of drift nets in 1997) to ensure viable fisheries have posed new challenges for the fishermen and the local communities, who have faced seasons of crisis and now have to envision sustainable futures. Today, fishermen are confronted with the consequences of decades of exploitation of the marine resources and the plastic litter, two big questions that deeply affect the Adriatic Sea. To face these global challenges, on 6 April 2019, the Italian Government approved a bill that reforms the previous law by making fishermen central actors in the collection of the plastic waste in the sea. The previous law (152/2006) put the fishermen in the paradoxical situation of risking being fined for ‘illegal transport of waste’ if they brought the waste found in sea and the plastic caught in their fishing nests to the port. The Museo della Regina, Municipality of Cattolica (Rimini) has an ethnographic section entirely devoted to naval archeology and the everyday lives of the fishing community. In this section there are unique gems including the first naval engine ever installed in Cattolica, precise models of the ships in different stages of construction, an actual section of a sailboat, and original sails and shipbuildres’ utensils. Building on the tangible heritage on the Adriatic seamanship collected in this section, the museum has developed an educational programme for school. Over the past few decades, the Museo della Regina has contributed to historical research and dissemination on the topic through conferences, public events, publications as well as a School of Naval history and Archeology (1995-2006) organized in collaboration with ISTIAEN. In 2002, it realized the documentary feature ‘Living Archives of the Sea’ (Archivi viventi del mare, Ceschi 2002), drawing on 14 interviews with the oldest fishermen collected in 1995. In 2016, the Museo della Regina dedicated the European Heritage Days precisely to the traditional fishing vessel ‘trabaccolo’ and to the intangible heritage surrounding it (Bordinzando col trabaccolo: storia, tecnica e conservazione della barca regina dell’Adriatico). However, the history of the motorization of the traditional Italian fisheries still needs to be fully investigated, through the analysis of the fading memories of the fishermen who lived an unprecedented socio-economic and ecological transormations. Sea people’s personal memories are part of an intangible heritage, with deep transregional historical dimensions, which can play a fundamental role in the historical reconstruction of past events. In addition to enhancing our shared knowledge of the past, this intangible heritage - if properly recovered and shared - has the potential to trigger inter-generational exchange, to raise public awareness of the historical roots of the present and to foster the imagination of sustainable futures. Contact details: Museo della Regina di Cattolica Via Pascoli, 23 47841 CATTOLICA (RN) Tel. +39. 0541 966577; e-mail: museo@cattolica.net; http://www.cattolica.net https://www.facebook.com/museodellaregina/

The story of the decades-long passage from the lugsail fishing boats to the motorized boats, gazed from the perspectives of the fishermen in Central Italy, has strong historical and transregional dimensions, which makes it an integral part of the history of the Adriatic Sea and the Mediterranean Sea more broadly. Since the ancient times, indeed, the Adriatic Sea has been a channel of communication and a space of mediation between different communities living along the Mediterranean shores (consider, for example, the influence of the Phoenician seamanship in the Aegean Sea in the V century B.C.). Wars, commerce and cultural exchanges significantly contributed to cross-cultural fertilization of local seamanship. The traces of these historical entanglements were vividly present - until the first decades of the XX century - in the cultures, languages, knowledge of the Sea peoples in the Mediterranean basin, and still reverberate in the testimonies of the older generations of fishermen in Central Italy. Recoveing and sharing this cultural heritage, embedded in the memories and life-worlds of the Sea People in Central Italy, can contribute to reinforcing a sense of belonging to the European common space in three main ways: first, by revealing the historical entanglements between different peoples and cultural traditions running through the Middle-Adriatic seamanship, second, by foregrounding the key role of the sea as a space of mediation and communication, and third, by raising awareness about the global challenges (such as the disrupting effects of massive exploitation of the marine resounces and the plastic litter in the sea) European countries are facing and the need to work toward a sustainable future. Our vision of cultural heritage, indeed, highlights its transformative potentials: its capacity to pave the way for inter-generation dialogue, to raise public awareness and to promote community engagement.