the Jewish Nation@Själagårdsgatan 19

In 1795 the Jewish congregation moved into a former auction room in Själagårdsgatan in Stockholm’s Gamla stan. It was the centre of Jewish life in Sweden for almost a century. It had a synagogue and a religious school, and the rabbi, cantor, and kosher butcher all lived on the premises. In the basement was a ritual bath, or mikva, and the kitchen baked the congregation’s matzo for Passover.

Själagårdsgatan was the headquarters of the Jewish Nation during its existence (1782–1838). It was where the elders of the community met to deal with religious and worldly questions of all kinds. It was here that all official business with the government and city was done. Formal complaints about discrimination were drawn up, official letters were answered. Under the Jewish Ordinance, a rabbinical court was to hear all civil cases to do with marriage, divorce, inheritance, and the like. The Jewish Nation in Själagårdsgatan was thus central to the lives of all Jews in Sweden in the early nineteenth century.

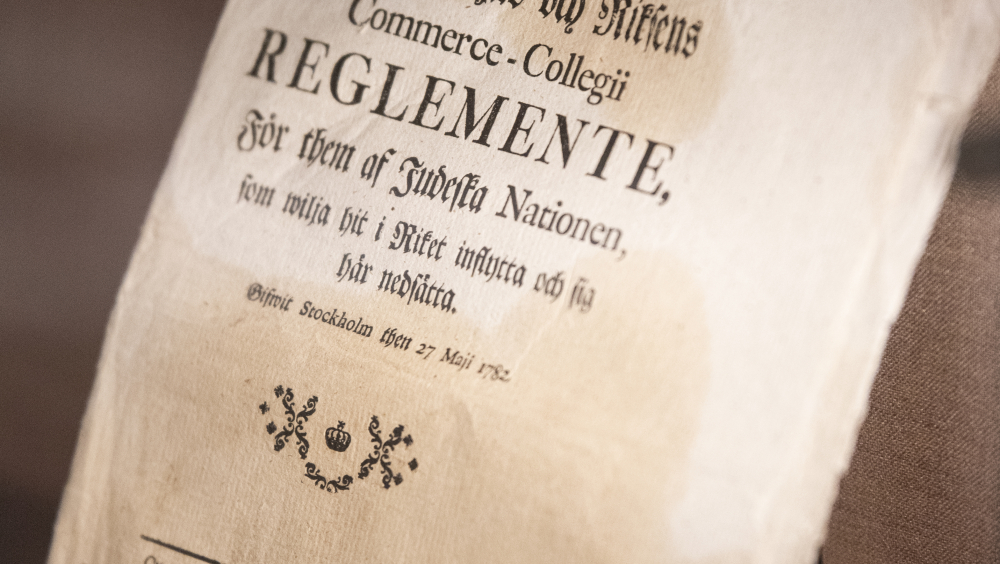

In 1779 foreigners were given the right to immigrate to Sweden and practise their religion freely. But the law did not go far enough, which was why in 1782 another was passed: the Jewish Ordinance. It copied Prussian regulations designed to control the Jewish population. Jews were only allowed to live in three cities: Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Norrköping. Jews were banned from working as craftsmen or joining guilds. They were expected to live apart and marry within their own community. All disputes were to be settled within the group. The Jews were to be the Jewish Nation, a state within a state.

In 1795 the Jewish congregation moved into a former auction room in Själagårdsgatan in Stockholm’s Old city. Själagårdsgatan was the headquarters of the Jewish Nation during its existence (1782–1838). It was where the elders of the community met to deal with religious and worldly questions of all kinds. It was here that all official business with the government and city was done. Formal complaints about discrimination were drawn up, official letters were answered. Under the Jewish Ordinance, a rabbinical court was to hear all civil cases to do with marriage, divorce, inheritance, and the like.

The Jewish Nation in Själagårdsgatan was thus central to the lives of all Jews in Sweden in the early nineteenth century. It was the centre of Jewish life in Sweden for almost a century. The congregation was responsible for its members being able to live a Jewish life. It had a synagogue and a religious school, and the rabbi, cantor, and kosher butcher all lived on the premises. In the basement was a ritual bath, or mikva, and the kitchen baked the congregation’s matzo for Passover.

From 1795, the property was first rented, then owned, by the Jewish nation. The synagogue was set up on the second floor where the auction room used to be. The synagogue had a women’s gallery and lectern with four gilded and sculpted columns, which still remains.

The façade towards Själagårdsgatan got its current decor with the round-arched, high windows in 1839. At the same time, some internal repairs and changes took place, among other things the roof of the synagogue was raised to its current 4.8 meters.

When the Jewish congregation left Själagårdsgatan in 1870 for a larger, new building in a more modern part of town, the synagogue became a chapel for the Seamen’s Mission. The directors, famous Swedish psalm writer Lina Sandell and her husband Carl Oscar Berg, also took over the furnishings.

20 years later, the property was leased to Nicolai police station, which remained for almost a hundred years, until 1972. On the ground floor were detention facilities and upstairs the police had their main office. The exterior of the house did not undergo any major changes in connection with this, but the interior floor plan was adapted to its new function. The former synagogue and chapel was divided by walls to create both interrogation rooms and work space for officers on duty. Eventually, the police station was converted into offices and housing.

On June 6, 2019 - on Sweden's national day – the new Jewish Museum was inaugurated in the place where Swedish Jewish history once began.

info@judiskamuseet.se

Stockholm's first synagogue represents an important historical event when the Jewish congregation in Sweden for the first time recieved the right to freely practice their religion in their own synagogue. It was housed upstairs in the house at Själagårdsgatan 19 and had, among other things, a still preserved women's gallery, which is also extremely authentic when so much else has been changed or removed.

As the first Jews in Sweden mostly came from Germany, the synagogue must also be seen in a wider European context. Many of the synagogues in Europe have been destroyed, but as Sweden was not physically affected by the second world war or the Holocaust, the building and its preserved ornaments remain intact. It is a unique treasure.

The authentic site carries historical layers and traces of existence - a journey through the Swedish-Jewish cultural heritage. The preserved synagogue contributes to broadening knowledge about the Swedish cultural heritage around one of Sweden's national minority groups and increases the diversity of culturally and historically valuable environments. As the Jewish museum is open to the public, a relatively unknown part of Swedish cultural heritage is made available to the general public for the first time.