The ‘Industry’ that unifies two cultures in one city: Ayvalik

Ayvalik, a city located in northwest Anatolia, has been at the forefront of olive-based industries since the 1880s which was an important Greek settlement under Ottoman rule. The city experienced a major turning point with the population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923, an event that caused dramatic changes in the political, demographic, and economic structure of all of Anatolia. The cultural diversity of different ethnic societies living together in the Ottoman State have a major impact on many Anatolian cities, and Ayvalik is one of the important ones in which the Rums[1] were dominant just before the 1923’s agreement (Ari, 1995; Cengizkan, 2004). Nonetheless, Ayvalik has maintained its importance through its ongoing olive-based industries and well-preserved historical urban fabric, the likes of which represents one of an exceptional example of living testimony of continuing land-use by Turks (Yildiz, 2017; Yildiz and Sahin Guchan, 2020). Although the industrial activities that were held in the 19th century traditional buildings within the city center were terminated in compliance with the environmental law in the 1980s, the olive oil production has continued to proceed outside the city center through modern processing technics. In parallel to these, industrial landscape of Ayvalik is accepted on the tentative list of UNESCO in April, 2017 as an outstanding example of social and economic structure of 19th-century industry based on olive-oil production in Western Anatolia (UNESCO, 2017). The city is an example of an active olive-based industry since the 19th century which reached its peak with the new operated factories on the coastline after the population exchange in 1923 (Sahin Guchan, 2008).

The story stems from two important facts regarding the city, the one is the city’s exceptional culture role-play to bridge two different but in the meanwhile similar cultures that are Turkish and Greek, the second is concerned inhabitants’ identity role-play on Ayvalik through olive industry by constituting its tangible and intangible industrial heritage today. The dialogue between inhabitants with different ethnic origins and the link to their hometowns is the key to describe and read the identity and the overall characteristics of the city. 1923 was the milestone for the historical trajectory of Ayvalik which was one of the cities that shares this destiny together with various number of Greek and Anatolian cities. In fact, each city represents different heritage story in relation to their historical process that occurred according to different dynamics. For example, some of Greek and Turkish cities and villages have similar urban aspects that make somebody to think if they were twin cities or same cities which offer a ‘DeJa’Vu’ sensation to the audience. Apart from the anterior development process of these cities before the population exchange which also caused this urban similarity, they were also developed and reshaped by their new users according to their ‘common thing’ that associated with those arrival and departure cities.

For the protagonist city for this story, Ayvalik, the ‘olive-based industry’ was seen that ‘common thing’ by the newcomers, and the overall industrial image had been strengthened and developed subsequently in time. They constructed new factories in addition to the existing ones, or they re-organized and modernized the existing ones according to their way of manufacturing. Today’s unique and exemptional characteristic of the city that was defined as industrial landscape of Ayvalik derives from the role of ‘industry’ as a ‘common’ culture for the newcomers which reshaped the primary image of the city. Pursuant to this, this dialogue among the city, industry and inhabitants caused the strengthening of industrial texture on urban characteristics of the city which also constitutes the Ayvalik industrial landscape today. To describe the overall industrial image of the city in the form of text, one of the pixel stories is presented.

[1] ‘Rum’ is defined as Greeks, orthodox, east romans of Anatolia, Greek speaking Christians under Ottoman rule. The word ‘Rum’ is derived from Romeus (Turkce Bilgi, n.d.)

Ertem Family is one of those migrants of 1923 who had been obligated to leave their hometown of Crete for starting their new lives in Ayvalik. After a month they had passed in a huge factory as a permanent stay from their arrival, with almost other twenty migrated families from diverse Greek cities, finally they had known their new properties by the Turkish officials. In compliance with the agreement, the distribution of the properties would be completed based on each family’s assets in their previous hometown, for example, a home and a factory building remained from previous users were approved by the government for Ertems. However, it was not always fair and equal for the other families which was also driven by the fortune. The remained factory that was previously used for small-scale olive-oil production and soap-making by the Rums, developed, and expanded subsequently according to the technological developments and Ertems’ preferences to facilitate the production process.

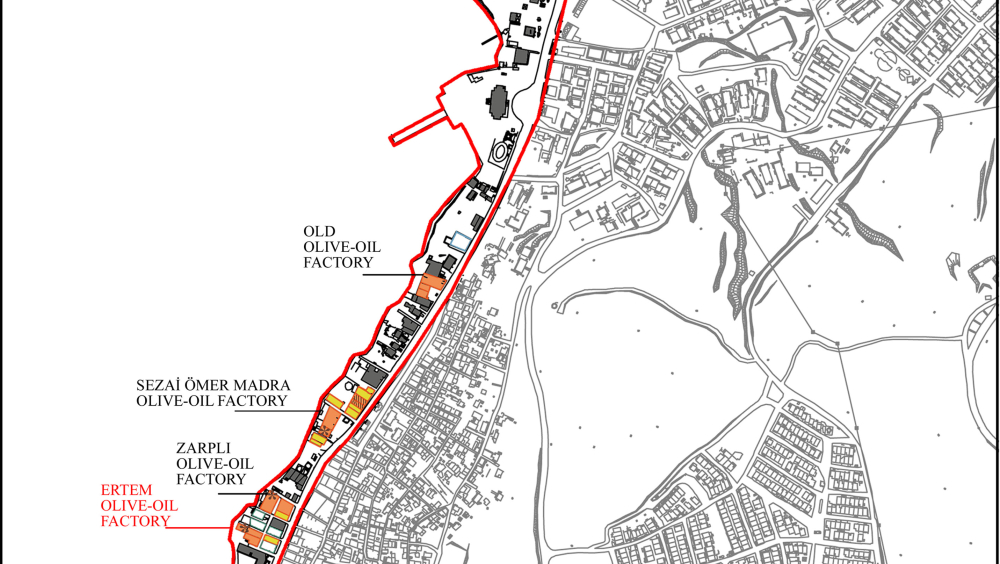

The reason behind the selection of this story intends to chart a pixel of the historical development process of medium-scale industrial heritage complexes of the city which define the important part of industrial urban texture constituting the northern silhouette along the coastline. Ertem Olive-Oil Factory that is the main subject of this story, is one of the industrial heritage buildings in Ayvalık with large program including olive-oil and side products such as soap and pirina -that was the waste parts of the olives produced during the olive-oil process to be used as fuel for the steam machines-. While there are large building complexes as the advanced ones which were kept functioning from the 19th century to the end of 1970s by making modernizations on production system such as Sezai Ömer Madra (the largest one), Kırlangıç and Vakıflar Olive-Oil Factory, there are also other medium-scale complexes such as Ertem Olive-Oil Factory which are smaller than abovementioned advanced ones used and developed by family enterprises that were mainly those immigrants. According to the records, the factory remained to the Ertems was constructed in 1910 by a Rum businessman, namely Anastasios Yorgolos, then it was transferred to ‘Emvali Metruka Idaresi’ during the exchange process. Soon afterwards, it was purchased by a banker, namely Kahraman Bahadır, and subsequently Guldenoğlu Family obtained the ownership until the exchange process completed. Finally, in 1952, the complex was approved as the property for Ertems to let them continue for their industrial activities in the following years.

Medium-scale factories along the coastline in Ayvalik with large program that includes olive-oil and side products are generally two-storied structures, some of which were developed based on the single-story workshops or depots remained from their previous Rum users for small-scale productions as their basic needs, while some of the others were originally constructed as two-storied complexes for larger scale manufacturing. In fact, it is not easy to make a typology of those industrial buildings as which were constructed for soap-making or mix-program including olive-based side products. Accordingly, the narratives of the previous users regarding the daily life that held in these places are the important sources to understand and chart the primary characteristics of industrial complexes of the city and their historical developments which define the main urban texture. Besides, they are also crucial to illuminate the olive-oil process and soap-making as cultural rituals operated in these structures that are the part of industrial heritage and archaeology which have shaped the architectural characteristics of the factories and their physical layouts.

The Ertems’ story was used by the author for different academic papers and MSc. thesis to illuminate various aspects of the factory, the olive-oil process and soap-making culture, and other works regarding the urban texture of Ayvalik. Based on their narratives on industrial activities that were held in the factory, two historical moments have come to the fore to understand the development of the preexisting layout of the industrial complex. According to this, the preexisting structure was composed of two different blocks, the one was constructed two-storied olive oil and soap factory, while the other was a single-story depot. When the complex was transferred to the Ertems, first, they proceeded several changes in compliance with the technological requirements of the time such as additional internal space for technical room to put the steam engine and addition of a furnace to fire the soap-boiling cauldron. Following this, they re-organized the existing layout according to their preferences of production process that they were following within their former property in Crete. For example, while the ground floor of the two-storied factory was started to be used for preparation stages for olive-oil manufacturing and the first floor was reserved for main processing, while on the other hand, the single-story depot was started to be used for olive-based side products such as soap-making and pirina. To do this, they added another floor on this block to better organize the side-process, the ground floor was dedicated to stack the pirina to become sold or to become used as fuel for steam engine, while on the other hand, the newly added first floor was reserved for timber angled grid flooring called ‘sabun tavlasi’ to dry the soap that obtained from the soap cauldron. The soap cauldron which was previously positioned in the preexisting two-storied block, was moved to the other block due to its working nature that necessitated to connect to the furnace. In fact, this technical equipment was conic in form, with the bottom part located in the technical room at the ground floor, and the upper part positioned soap-making area at the first floor. In the following years, a new block was also constructed for an office for selling purposes (Yildiz and Sahin Guchan, 2020).

The importance of this story is that the narratives of those people who experienced and manifested these changes as the first actors are not only illuminate and help to make a typology of those industrial heritage structures by identifying the urban texture and industrial characteristics of the city but also concretize the city’s urban history through intangible values. For example, they also narrated that until the 1980s when the industrial activities were terminated through the environmental law, the northern coastline zone of the city that was defined by those medium-scale factories, represented the strong industrial image of the city not only via those industrial complexes and chimneys[1], but also through the sensations such as strong olive-oil smell and the voice of soap stamps. In fact, the city that includes various number of those medium-scale industrial factories, and they are still waiting to discover other pixel stories from their former users.

[1] Chimneys of Ayvalik has been submitted as an event organized by E-FAITH for ‘May-Chimney Month’ in 2019, which was launched for the chimney focusing on industrial heritage and heritage promotion similar to the event of #Ode2Joy Challenge created by Europa Nostra and Placido Domingo for the 9th of May, the Europe Day. [see http://industrialheritage.eu/EYCH2018/May].

The population exchange between Greece and Turkey that occurred in 1923 represents one of the important milestones in the historical development of these nations. This drastic change in two different cultures, while it left several traumatic traces to those forced immigrants via their feelings, while on the other hand, it also influenced the culture in different manners which was existed before their arrivals. For the presented story regarding the city of Ayvalik, the intention focuses on highlighting how this traumatic event had caused the evolvement of the European culture by incarnating with other spheres producing their tangible and intangible consequences which are considered as heritage today. The industrial landscape of Ayvalik is an exemptional living testimony of continuing land-use by Turks which has been shaped through the ‘olive-based industry’ as a common culture.