Creative Catalyst: The Generator's European Arts Journey

The Generator in Loughborough represents a significant transformation in heritage - from engineering and education to dynamic cultural space. Through the visionary leadership of the late Kev Ryan, this architectural landmark was reimagined as an arts and culture centre, becoming a focal point of cultural evolution spanning seven decades.

Our story documents the oral histories of individuals whose creative journeys intersected with this space from the 1950s to the present day. From Colin Salsbury, our 96-year-old witness to post-war cultural rebuilding, to historians like Ernie who connects us to industrial heritage through accounts of Morris Crane and its German business partnerships (including a remarkable story of targeted Zeppelin bombing during WWI), these voices form a rich collection of shared experience.

The Generator has consistently attracted and fostered those at the forefront of cultural movements - David Salsbury’s experiences of 1960s-70s counterculture; educators like Pete Wheeler shaping fine art education at one of the last Monotechnics in the UK; Frances Ryan alongside Kev Ryan championing community art decades before it was rebranded as "participatory art."

Throughout its history, the Generator has been a gathering place for diverse voices - punks, radical feminists, anti-nuclear activists, anti-apartheid campaigners, and acid house devotees - reflecting parallel movements across creative spaces. The building itself embodies the transformation of industrial architecture into cultural infrastructure.

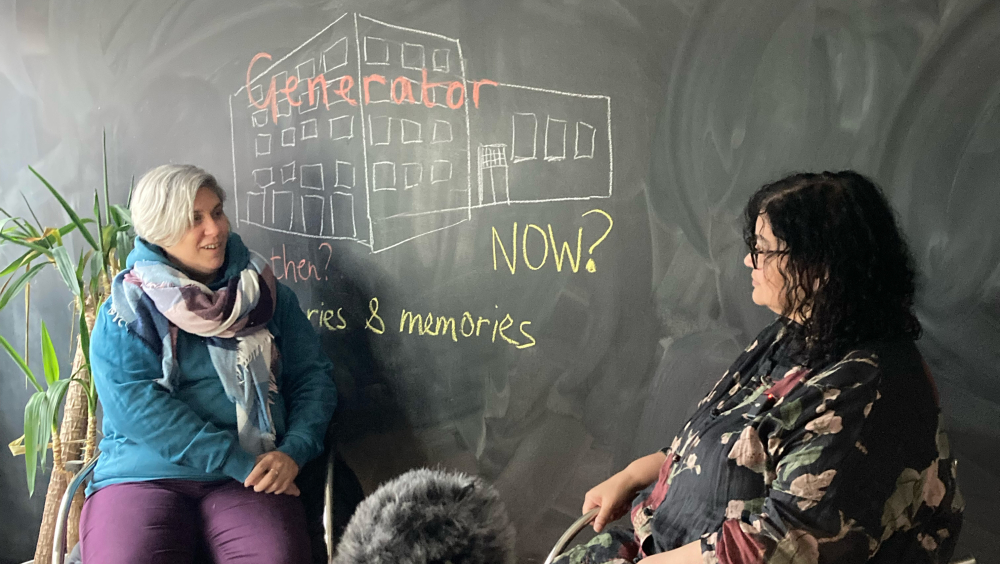

These stories, collected through our "Stories and Memories" heritage project, reveal how the arts have attracted neurodivergent individuals, minority groups, and subcultures, creating space for diverse expression within a shared artistic tradition. By preserving these oral histories, we illuminate not just a local legacy, but a journey of creative resistance, expression, and renewal that resonates beyond our borders.

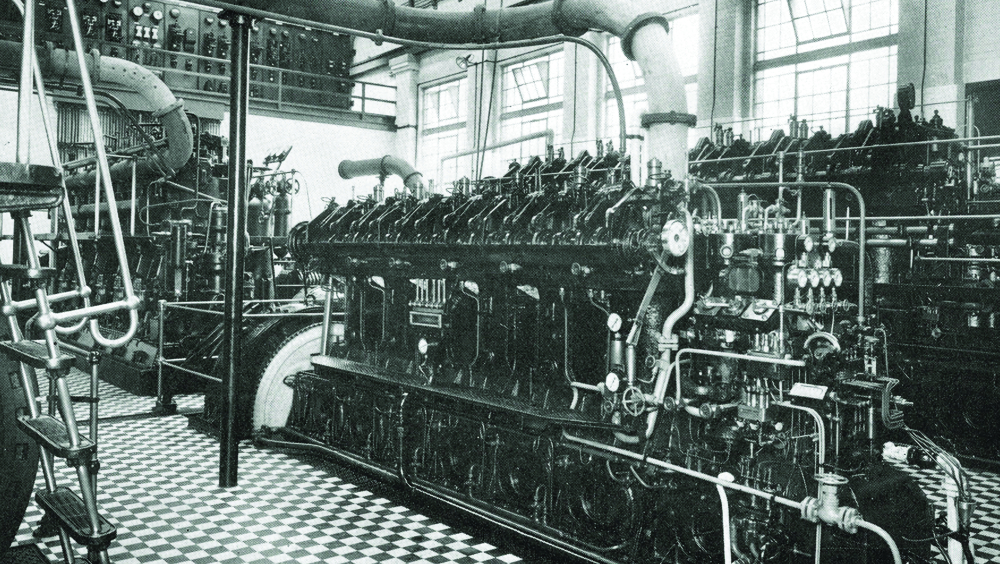

The Generator stands as a testament to industrial heritage reimagined through creativity. Originally designed during the era of Herbert Schofield, who transformed a small technical institute in 1910 into what would eventually become Loughborough University, this building has witnessed and fostered cultural evolution across multiple generations.

Our oldest interviewee, Colin Salsbury, at 96 years old, carries memories stretching back to the 1950s. His recollections of the art college during this period reflect the broader context of post-war cultural reconstruction. While he describes himself as coming from a time of "traditional values," his presence at the art college hints at the seeds of creative exploration that would flourish in subsequent decades. Colin's testimony bridges the gap between industrial heritage and creative transformation that occurred across post-war cities.

Ernie, a local historian and authority on Herbert Schofield, provides crucial context about the Generator's industrial origins. His intimate knowledge of Morris Crane, a UK-owned firm with German business partnerships, illustrates the interconnected nature of industrial development before being severed by conflict. Ernie shares a remarkable anecdote about how after the owner of Morris Crane's German business partner was sent home at the outbreak of WWI, the only Zeppelin bombing raid on Loughborough "coincidentally" targeted the Morris Crane site. This story encapsulates complex industrial relationships fractured by war – where cooperation turned to conflict before eventually returning to collaboration.

By the 1960s-70s, The Generator had evolved into a space embracing countercultural movements. David Salisbury's "alternative experience" during this period mirrors similar artistic awakenings in spaces from California to Berlin and parallels Alvin Toffler's idea of the third wave that followed the industrial revolution and started in the 1960s. His stories reveal how countercultural ideas permeated even smaller British towns, creating networks of alternative thinking that transcended traditional boundaries.

The 1980s brought new waves of political engagement through art. Evelyn Silver tells of her memories of the Generator becoming a space for facilitating protest art responding to nuclear threats and Pasha Kincaid’s memories include supporting anti-apartheid movements. These activities connected Loughborough artists to networks of political activism, where creative expression became a tool for addressing shared concerns about peace, equality, and justice.

Pete Wheeler, as Head of Fine Art, inhabited the space where traditional artistic education evolved to embrace new forms and philosophies, as pioneered in the Bauhaus movement in Germany - was involved in a new precedent of teaching art and design ideals without a governing body or syllabus. His leadership during this transitional period navigated tensions between classical traditions and emerging practices – a negotiation happening simultaneously across art schools responding to rapid cultural change.

Frances Ryan's work exemplifies the rise of community art practice that would eventually gain recognition as "participatory art." This transition from marginalised community-focused creativity to institutionally recognised practice reflects broader policy shifts toward cultural democratisation in the late 20th century. Her work, alongside the vision of her late husband Kev Ryan (described as "a pioneer and visionary" who explored community art "when it was shunned by the whole art world"), positioned the Generator within movements to make art more accessible and community-centred.

Throughout its evolution, the Generator consistently provided space for those on society's margins. The arts have always been synonymous with counter culture and attracted alternative folk, neurodivergent individuals, and minority groups representing niche subcultures. This inclusive approach has nurtured diversity and provided platforms for marginalised voices.

The summer exhibitions at the Generator in the 90’s as organised by Artspace by Nita Rao and Tony Thore, represent the continuing tradition of community engagement. Their work builds upon the legacy of making art public and accessible, continuing conversations about the role of creativity in community cohesion.

Today, the Generator's transformation into an arts and culture centre fulfils Kev Ryan's vision while participating in a wider phenomenon of repurposing industrial architecture for cultural use. From the Tate Modern in London to the Matadero in Madrid, from the Zollverein in Germany to Kaapelitehdas in Helsinki, and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, industrial buildings have often found new life as creative spaces. The Generator's journey is part of this shared narrative of adaptive reuse that honours industrial heritage while creating infrastructure for contemporary cultural expression.

By collecting and preserving these diverse oral histories, we create not just a local archive but a document of cultural evolution as experienced through individual lives. Each interview captures a fragment of shared heritage – from industrial development and wartime experience to countercultural movements, political activism, and community arts. Together, they reveal how local spaces both reflect and contribute to broader cultural currents beyond their immediate geography.

Sample interviews -

Interview with Pete Wheeler: https://youtu.be/p1sNsEa9430

Interview with Frances Ryan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S9uHa4bNKeI

Interview with Jenny Stevenson: https://youtu.be/jr824y96AQ4

The Generator's story embodies multiple facets of European dimension, connecting local experiences to continent-wide cultural movements and shared heritage. Its architectural transformation from industrial space to creative centre represents a pattern repeated across Europe, where former factories, power stations, and warehouses have become cultural landmarks – from LX Factory in Lisbon to Telliskivi in Tallinn. This adaptive reuse of industrial heritage for cultural purposes reflects a pan-European approach to preserving architectural history while meeting contemporary needs.

The oral histories span seven decades of European cultural evolution, documenting how continental movements manifested locally. Ernie's account of the Morris Crane company with its German business partnership illuminates pre-WWI European industrial cooperation and the subsequent conflict that reshaped the continent. The Zeppelin bombing story provides a tangible connection to shared European war experiences that have influenced collective memory and identity.

Throughout different eras, the Generator connected to transnational European cultural movements – from 1960s-70s counterculture to 1980s political activism around nuclear disarmament and anti-apartheid work, to 1990s club culture. These parallel developments across European creative spaces created networks of shared values, aesthetics, and approaches that transcended national boundaries.

The Generator's consistent embrace of diversity – welcoming "alternative people, neurodivergent, minority groups" and various subcultures – reflects the broader European journey toward recognising and celebrating cultural diversity. Kev Ryan's pioneering work in community art, initially "shunned by the whole art world" before being embraced as "participatory art," mirrors similar trajectories across Europe where marginalised practices eventually influenced mainstream cultural policies.

By preserving these stories, we document not just local heritage but a lived experience of European cultural development from multiple perspectives. The intergenerational nature of these testimonies – from 96-year-old Colin to contemporary practitioners – creates a continuity of memory that strengthens understanding of shared European cultural identity while highlighting the distinctive characteristics of local expression within that broader context.